| |

Top News

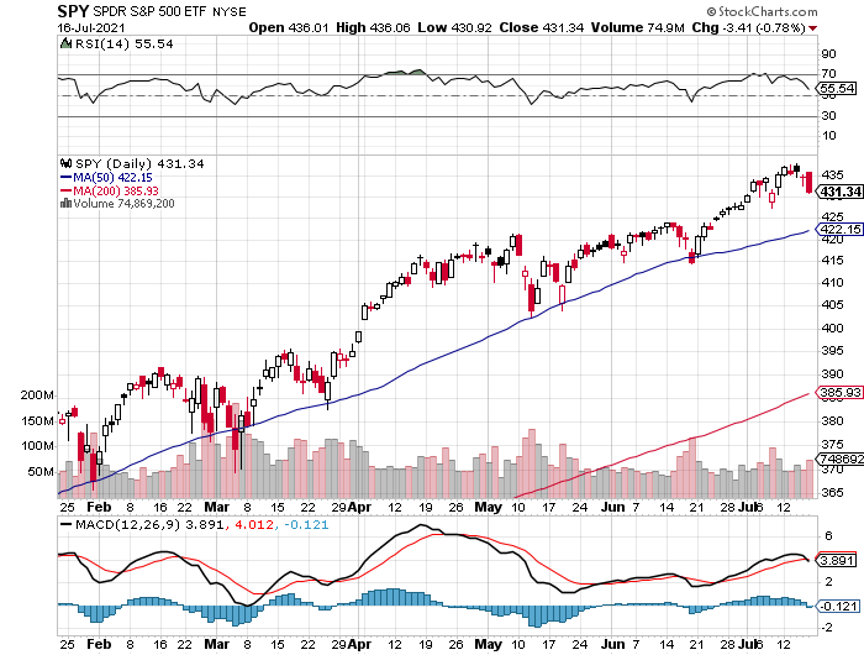

Shutterstock Stocks fell Friday to push the major market indexes into the red for the week, as rising concerns over inflation outweighed strong retail sales data and better than expected quarterly earnings reports from the big U.S. banks. The major market averages all snapped three-week winning streaks, with the Dow dropping 0.5%, the S&P 500 slipping nearly 1% and the Nasdaq Composite closing 1.8% lower. But the bond market continues to buck inflation fears, as the 10-year U.S. Treasury yield fell to around 1.30%. Crude oil slumped to its biggest weekly loss since mid-March as markets face the prospect of extra supplies from OPEC producers, and a stronger dollar also hurt the appeal of commodities priced in the U.S. currency this week.

| | Space

Congrats to Richard Branson!

The 70-year-old founder of Virgin Galactic (NYSE:SPCE) rode the VSS Unity into the lower reaches of space on Sunday morning following a 17-year quest towards suborbital space tourism. "For the next generation of dreamers, if we can do this, just imagine what you can do," he said before unlatching his seat belt. Branson can now claim victory in the "billionaire space race" by riding his own spacecraft, though Blue Origin's (BORGN) Jeff Bezos will take his own ride to space next week, while Elon Musk has been in a class of his own by concentrating on the orbital arena and beyond via SpaceX (SPACE). Bigger picture: Branson believes that there is a market to carry as much as 2M people on suborbital spaceflights priced in the $250,000 to $500,000 range, meaning a $1T market at the upper level. The industry could also expand. "There's room for 20 space companies to take people up there," Branson said in a recent interview. "The more spaceships we can build, the more we can bring the price down and the more we'll be able to satisfy demand and that will happen over the years to come." Responding to the latest developments, shares of Virgin Galactic opened the week in the ionosphere, before tumbling back to Earth. Galactic was among the recent generation of space companies to go public via a SPAC in 2019, but it hasn't stopped there. Over the past two months, rocket builder Astra Space (NASDAQ:ASTR) and satellite broadband firm AST SpaceMobile (NASDAQ:ASTS)have begun trading, while companies like Rocket Lab, BlackSky, Spire Global and Momentus are expected to follow suit. What to watch next: Jeff Bezos will make a run at suborbital space on July 20, launching aboard Blue Origin's New Shepard rocket. The system launches vertically from the ground, compared to Virgin Galactic's SpaceShipTwo/VSS Unity, which is released mid-air and glides back to Earth for a runway landing. Blue Origin has also emphasized that it's flying above the Karman Line, a boundary 62 miles above sea level that's commonly referred to as the beginning of space (Galactic's flight only reaches 50 miles up, an area the FAA says still makes you an astronaut).

| | Sponsored By Fundrise

Building Blocks to Real Estate Investing

Remember when snagging real estate was an unattainable date, who, try as you might, your little engine never could? Now it can. With Fundrise, invest today in the future you imagined for tomorrow. Quality assets; Low fees; Powered by super smart technology.

Remember when snagging real estate was an unattainable date, who, try as you might, your little engine never could? Now it can. With Fundrise, invest today in the future you imagined for tomorrow. Quality assets; Low fees; Powered by super smart technology.

Crowd-funded investment opportunities offer easy access to institutional-caliber real estate. Fundrise can help you develop a diversified portfolio strategy across numerous investment funds. More than 150k active investors have earned $100M+ in net dividends so far.

Start building wisely today.

| | Financials

Bank results

The second quarter earnings season formally kicked off this week as JPMorgan (NYSE:JPM) and Goldman Sachs (NYSE:GS) released results on Tuesday. Other major financial institutions also reported, including Bank of America (NYSE:BAC), Citigroup (NYSE:C) and Wells Fargo (NYSE:WFC) on Wednesday, and Morgan Stanley (NYSE:MS)on Thursday. While the banking industry unveiled some blowout results,much of that growth was measured against a time when much of the economy was brought to a pandemic standstill, and the stocks inched marginally higher. Some highlights: Goldman: Investment banking revenue soared 36% Y/Y to $3.6B, helped by financial advisory, corporate lending and underwriting units. Morgan Stanley: Equities trading outperformed in Q2, producing $2.83B in revenue. Citi: Quarterly profit surged more than 5x to $6.2B, driven by the lower cost of credit.

| | Commodities

Timberrr!

Supply chain shortages, coupled with a swift economic recovery, saw prices of many items soar during the pandemic. One of the most notable increases was for lumber, which is a significant material for many industries including homebuilding. While the historic run has come to an end, it still could take a while for prices to go back to their pre-pandemic levels. Update: Lumber futures (LB1:COM) surrendered all of their astronomical 2021 gains on Monday, settling down 5.6% to $712.90 per 1,000 board feet in Chicago. Supply and demand are behind the latest moves as homebuilders and DIYers started to pare back on projects due to prices, while sawmills upped their production levels for the same reason. In fact, new home construction and home improvement sales in May were 8.8% and 8.1% lower than their highs seen in March. At one point this year, lumber futures were even trading as high as $1,733.50 per 1,000 board feet, more than quadruple the level of a year earlier. "We could be in for a few more weeks of declines. Mill production has ramped up as the labor related issues from COVID dissipate," said Dustin Jalbert, senior economist at Fastmarkets RISI. "There's a lot of inventory buildup at the mills that has to clear." Wood has even turned lower as wildfires rage and railcars are gridlocked in British Columbia, a major producing region. Where do we go from here? Lumber futures have mostly in the $200-$400 per 1,000 board feet range before the pandemic, and each dip in the wholesale market could take weeks or months to be reflected in store aisles. Lumber prices are undergoing a "paradigm shift" and are in the process of determining a new and much higher average price level as a result, according to lumber trading strategist Greg Kuta of Westline Capital Strategies. Scott Reaves of Domain Timber Advisors even forecasts prices could stay above $500 per 1,000 board feet for the next 5-8 years due to robust homebuilding across the U.S. (15 comments)

| | Central Banking

Powell on the Hill

Fed Chair Jerome Powell was in the hot seat on Wednesday and Thursday as he headed before Congress for his semiannual testimony on monetary policy. Inflation, which was once the elephant in the room, is became the most heated topic at the grilling following data on rising costs across the American economy. The Consumer Price Index grew at its fastest clip since August 2008, climbing 5.4% year-over-year versus a forecast of 4.9%. Until recently, the Fed has stuck to the script that inflation will be "transitory," though some rumblings over that outlook are being heard at the FOMC and broader investing community. Modest inflation can be good, but when things grow too fast and exceed a nation's fundamental capacity, the economy can overheat. When things slow down, a recession can hit, and central banks may attempt to raise interest rates before then to lower the amount of spending and borrowing in the economy. "This is a shock going through the system associated with reopening of the economy, and it's driven inflation well above 2%. And of course, we're not comfortable with that," Powell told lawmakers. "To the extent it is temporary, then it wouldn't be appropriate to react to it, but to the extent it gets longer and longer, we will have to continue to reevaluate the risks that would affect inflation expectations." Thought bubble: While we've seen price increases before, most of them were taking place in areas heavily hit by the pandemic. Those included building materials and travel-related costs, which were hit by supply chain problems and shutdowns, but the most recent report suggested that these increases are broadening out. Core inflation (excluding food and energy) came in at 4.5%, marking the largest increase since September 1991.

| | Automotive

End of the combustion engine?

We reported on the discussions last month, but the European Commission this week proposed a date to call time on the internal combustion engine. Sales of new cars and vans that produce CO2, including plug-in hybrids, would be banned as of 2035, meaning "almost 100%" of vehicles on the road would be emissions-free by 2050. While the decision would force the EV revolution upon European automakers, some are already planning moves of their own. In June, Volkswagen (OTCPK:OTCPK:VWAGY) paved its way toward an EV future by pledging to halt sales of ICE vehicles in Europe by 2035, while Ford (NYSE:F) has said it will only sell EVs in Europe by 2030. Volvo (OTCPK:OTCPK:GELYF) is retiring the ICE and hybrids by the same year and Honda (NYSE:HMC) announced plans to phase out gas-powered cars by 2040. Meanwhile, Stellantis (NYSE:STLA) is no longer planning to invest in the development of new internal combustion engines, while General Motors (NYSE:GM) will stop building polluting vehicles by 2035. European Green Deal: "To ensure that drivers are able to charge or fuel their vehicles at a reliable network across Europe, the revised Alternative Fuels Infrastructure Regulation will require Member States to expand charging capacity in line with zero-emission car sales, and to install charging and fueling points at regular intervals on major highways: every 60 kilometers for electric charging and every 150 kilometers for hydrogen refueling," the European Commission said in a statement. Just don't catch fire... General Motors on Wednesday told owners of 2017-2019 Bolt EVs not to park their vehicles inside or charge them unattended overnight after two of the EVs went up in flames. The cars had even been repaired as part of a recall of 69,000 vehicles that were flagged for fire risks, but that didn't seem to help. Other EV rollouts have also been interrupted by fires involving lithium-ion batteries, including Ford, BMW and Hyundai (OTCPK:OTCPK:HYMTF), which have issued recalls in recent months for new battery-powered models. (608 comments)

| |

U.S. Indices

Dow -0.5% to 34,688. S&P 500 -1.% to 4,327. Nasdaq -1.9% to 14,427. Russell 2000 -5.2% to 2,161. CBOE Volatility Index +14.% to 18.45.

S&P 500 Sectors

Consumer Staples +1.3%. Utilities +2.6%. Financials -1.6%. Telecom -0.3%. Healthcare -0.2%. Industrials -1.5%. Information Technology -0.6%. Materials -2.4%. Energy -7.7%. Consumer Discretionary -2.6%.

World Indices

London -1.6% to 7,008. France -1.1% to 6,460. Germany -0.9% to 15,540. Japan +0.2% to 28,003. China +0.4% to 3,539. Hong Kong +2.7% to 28,082. India +1.4% to 53,140.

Commodities and Bonds

Crude Oil WTI -4.2% to $71.46/bbl. Gold +0.1% to $1,812.6/oz. Natural Gas +0.1% to 3.679. Ten-Year Treasury Yield +0.3% to 133.84.

Forex and Cryptos

EUR/USD -0.56%. USD/JPY -0.08%. GBP/USD -0.91%. Bitcoin -6.%. Litecoin -10.1%. Ethereum -11.2%. Ripple -7.1%.

Top Stock Gainers

State Auto Finl Corp (NASDAQ:STFC) +191%. Red Cat Holdings Inc (OTCQB:RCAT)+137%. Datasea Inc (NASDAQ:DTSS) +71%. Bon Natural Life Limited (NASDAQ:BON)+63%. Mediaco Holding Inc Cl A (NASDAQ:MDIA) +62%.

Top Stock Losers

Precision Drilling Corp (NYSE:PDS) -17%. Amyris Inc (NASDAQ:AMRS) -17%. Cbdmd Inc (NYSE:YCBD) -17%. Bright Health Group Inc (NYSE:BHG) -17%. Englobal Corp (NASDAQ:ENG) -17%.

Where will the markets be headed next week? Current trends and ideas? Add your thoughts to the comments section.

| |

| |

| | �