.

That region of the world is changing, China is having greater influence. With such economic prosperity comes a greater thirst for power. Japan does not have it easy going forward, for damn sure

http://www.japantimes.co.jp/opinion...sias-best-friends-shape-an-axis/#.VA3U_FV0w5s

good read, shortened version below,

Rarely before in recent years has Japan gone so much out of its way to welcome a foreign leader as it did when receiving India’s new prime minister, Narendra Modi (or NaMo to his fans), who started his tour from Kyoto

The rationale bringing Japan and India closer together is powerful: If China, India and Japan constitute Asia’s strategic triangle with unequal sides — China representing the longest side, Side A, India Side B, and Japan Side C — the sum of B plus C will always be greater than A. In the absence of a Japan-India axis, the rise of a Sino-centric Asia could become inevitable.

Containing China, however, is not an option. China is the largest trading partner of both Japan and India, which cannot afford to disrupt their relationship with Beijing. Nor are India and Japan seeking to forge a military alliance in which each will be obligated to come to the defense of the other.

The key issue for India and Japan is how to address Asia’s current power disequilibrium, which has arisen because of the rapid rise of an increasingly assertive China that is seeking to disturb the territorial and maritime status quo. An entente between Asia’s two main democracies can help restore a fair degree of equilibrium to the power balance.

Abe, 59, and Modi, 63, represent the best chance for Japan and India to establish such an entente. Ideologically, Abe and Modi are soul mates, sharing similar political values, including market-oriented economics, soft nationalism, a proactive foreign policy, and a new Asianism that seeks to promote a web of interlocking strategic partnerships among important democracies in the Asia-Pacific. The two belong to the 1950s generation, share the zodiac sign of Virgo, and regard each other as friends.

Indeed, like two buddies meeting after a long time, Modi and Abe greeted each other with an effusive hug and glowing and beaming smiles.

By contrast, Modi’s predecessor, the octogenarian Manmohan Singh, was a generation older than Abe, who greeted him with the customary handshake each time they met.

International-relations theory assumes that interstate relations are shaped by impersonal forces, especially cold calculations of national interest. In truth, history is determined equally, if not more, by the role of personalities, including their personal strengths and weaknesses and their search for national security and respect.

The Abe-Modi affinity has been fostered both by personal chemistry and hardnosed calculations about the importance of Indo-Japanese collaboration in their plans to revitalize their country’s economy and security and restore national pride. Modi’s personal rapport with Abe was built during his 2007 and 2012 visits to Japan as chief minister of the western Indian state of Gujarat.

In a reflection of their close bond, Abe follows only three people on Twitter: his outspoken wife Akie, author-turned-politician Naoki Inose and Modi. “I am eagerly awaiting your arrival in Kyoto this weekend,” Abe tweeted to Modi last Friday, declaring, “India has a special place in my heart.” Earlier, in a tweet in Japanese and English, Modi expressed “excitement” over his impending meeting with Abe, adding he “deeply respects” Abe’s leadership and “enjoys a warm relationship with him.”

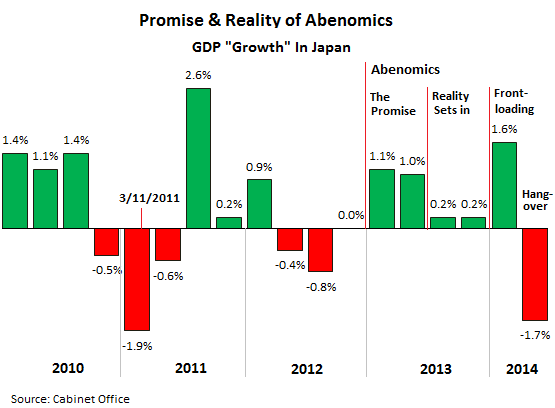

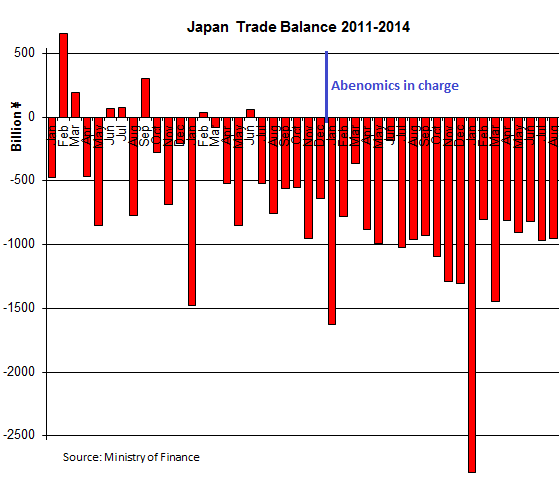

Abe sees India as the key to expanding Japan’s security options beyond its current U.S.-centric framework, while Modi views Japan as the engine that can drive India’s “Look East” strategy to success. “Abenomics” and “Modinomics” are both geared to the same goal — reviving laggard growth — yet they need each other’s support for success.

Whereas Tokyo sees India as important to its own economic-revival strategy, India looks at Japan as a critical source of capital and commercial technology and a key partner to help upgrade its manufacturing and infrastructure.

India — the biggest recipient of Japan’s Official Development Assistance, which is currently funding more than 60 Indian infrastructure projects — has become the largest destination for Japanese foreign direct investment (FDI) among major industrialized nations.

The path is now opening up to Japanese exports of weapon systems and nuclear power equipment to India, the world’s largest arms importer and one of the few countries still wedded to building new commercial nuclear plants in the post-Fukushima era.

The two countries’ dissimilarities actually create opportunities to generate strong synergies through economic collaboration. Japan has a solid heavy manufacturing base, while India boasts services-led growth.

India has the world’s largest youthful population, while Japan is aging more rapidly than any other major developed country. Whereas Japan has financial and technological power, India has human capital and a huge market for goods and services.

Japan clearly has an interest in a stronger, more economically robust India. Just as Japan assisted China’s economic rise through large-scale aid, investment and technology transfers for over three decades — a role obscured by the flare-up of territorial and other bilateral disputes in recent years — it is ready to help India become an economic powerhouse on par with China.

China, by contrast, has little interest in aiding India’s economic ascent. Beijing boasts a booming trade with New Delhi, but that commerce bears a distinct mercantilist imprint and shows India in an unflattering light: China exports three times as much as it imports and treats India, like Africa, as a raw-material appendage of its economy. This asymmetry is made more glaring by China’s minuscule foreign direct investment in India.

The present pattern of Chinese companies merely exporting finished goods in increasing quantities to India is not sustainable. A challenge for Modi is to calibrate China’s India-market access to progress on bilateral political, territorial and water disputes, or else Beijing will fortify its economic leverage against New Delhi.

In fact, China makes not-so-subtle efforts to block the rise of India and Japan, including by stepping up military pressure on them and opposing the expansion of the U.N. Security Council’s permanent membership. Japan and India thus have a shared interest in working together to restrain China’s exercise of its rapidly accumulating power, which risks sliding into arrogance.

The Japan-India relationship — characterized by “only good will and mutual admiration,” in Modi’s words — holds the potential to catalyze the two countries’ emergence as world powers while reshaping Asian geopolitics and instituting power stability.

The process to tap that potential is just beginning. Modi urged that the two countries should “strive to achieve in the next five years their relationship’s unrealized potential of the last five decades.” To that end, India and Japan have established a special new mechanism — a two-plus-two consultative framework on diplomacy and defense involving their foreign and defense ministers together.

Modi’s watershed visit has not only helped to define the parameters for closer Indo-Japanese collaboration through landmark accords but also sets in motion the addition of concrete strategic content to a relationship embodying Asia’s emerging democratic axis.