You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Tom Steyer (makes the Koch bros look like saints)

- Thread starter russ1945

- Start date

Seriously Russ, Soros has been giving billions for years and what does he have to show for it.

I’m thinking he expected a better ROI. I know I would have.

He is getting very old and wants to see socialism and a one world gov before he dies. Money is simply a means to an end for him. If the Dem's lose the Senate and the next Pres election no amount of money will allow him to see his goal reached before he dies.

He is getting very old and wants to see socialism and a one world gov before he dies. Money is simply a means to an end for him. If the Dem's lose the Senate and the next Pres election no amount of money will allow him to see his goal reached before he dies.

That would certainly be a good thing.

Koch Bros are evil say the libtards but Soros and Steyer are not. Hmmm. You just can't make this stuff up.

First off, you make yourself look stupider than you already are by using the term Libtards.

Second, Big Money controlling elections in the shadows is evil, no matter what side is doing it. I've made my position VERY clear on that. But you think The Koch's are fine, and refuse to even do any research whatsoever on their influence, while Soros and Steyer are evil. That's why you're a partisan hack and a Hypocrite and an Allinsky, whatever the hell that is.

Love how you capitalize libtards. Giving it a proper name...good start.First off, you make yourself look stupider than you already are by using the term Libtards.

Second, Big Money controlling elections in the shadows is evil, no matter what side is doing it. I've made my position VERY clear on that. But you think The Koch's are fine, and refuse to even do any research whatsoever on their influence, while Soros and Steyer are evil. That's why you're a partisan hack and a Hypocrite and an Allinsky, whatever the hell that is.

Maybe you should read Saul Alinsky's 'Rules for Radicals'

Educate yourself, you may just change your mind about what's taking place.

His goal for the Rules for Radicals was to create a guide for future community organizers to use in uniting low-income communities, or “Have-Nots”, in order to empower them to gain social, political, and economic equality by challenging the current agencies that promoted their inequality.[SUP][1][/SUP] Within it, Alinsky compiled the lessons he had learned throughout his personal experiences of community organizing spanning from 1939-1971 and targeted these lessons at the current, new generation of radicals.[SUP][2][/SUP]

Love how you capitalize libtards. Giving it a proper name...good start.

Maybe you should read Saul Alinsky's 'Rules for Radicals'

Educate yourself, you may just change your mind about what's taking place.

His goal for the Rules for Radicals was to create a guide for future community organizers to use in uniting low-income communities, or “Have-Nots”, in order to empower them to gain social, political, and economic equality by challenging the current agencies that promoted their inequality.[SUP][1][/SUP] Within it, Alinsky compiled the lessons he had learned throughout his personal experiences of community organizing spanning from 1939-1971 and targeted these lessons at the current, new generation of radicals.[SUP][2][/SUP]

I know all I need to know about Saul. He's irrelevant. Since I have no desire to be a Community Organizer, and have no desire to be a radical, I don't need to read the rules of how to become one. Thanks anyway. Perhaps the guys who "organized" Operation American Spring should read it though. They need all the help they can get at being effective radicals.

[h=2]Bruce Braley Flip-Flops on Keystone Pipeline[/h]Braley now benefitting from outside group funded by Tom Steyer

Share

Tweet

Email

U.S. Senate candidate Bruce Braley / AP

U.S. Senate candidate Bruce Braley / AP

BY: Daniel Wiser

May 21, 2014 4:54 pm

Iowa Democratic Senate candidate Bruce Braley reversed his stance on the Keystone XL pipeline last year and is now benefiting from spending by an outside group funded by a billionaire who opposes the project, according to reports.

Braley, a four-term congressman, initially voted in April 2012 to expedite construction of the pipeline. The measure was part of a temporary funding extension for federal transportation projects.

Braley praised the pipeline at the time in a statement: “The pipeline project is an opportunity to create thousands of jobs in Iowa and the Midwest and reduce our dependence on Middle Eastern oil. Environmental concerns must be addressed, and this bill provides an avenue to air those concerns to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission.”

“Keystone XL has attracted rare bipartisan support because of the enormous economic benefits it will provide,” he added. “It should move forward quickly once it’s approved.”

However, Braley voted against construction of the pipeline when a House bill passed last May. He announced his candidacy for the Senate last February.

Recent spending by groups that support Braley has raised questions about whether he switched his position on Keystone to benefit his campaign.

Senate Majority PAC, a Super PAC that aims to maintain a Democratic majority in the Senate and is run by former staffers for Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (D., Nev.), has spent almost $550,000 in support of Braley, according to the Center for Responsive Politics.

The New York Times reported on Saturday that Tom Steyer, a billionaire climate activist and former hedge fund manager, recently contributed $5 million to the Senate Majority PAC—making him the single largest contributor to the Super PAC this year.

Steyer has pledged to spend $100 million ahead of the midterm elections on climate issues, including efforts to block construction of the pipeline. He also has his own Super PAC, NextGen Climate Action.

Steyer is reportedly targeting states such as Florida, Iowa, and Virginia.

“A contribution to Senate Majority PAC, the way they spend it and use it, will be consistent with the criteria that we use to choose our states,” said Chris Lehane, a spokesman for Steyer, in an interview with the Times.

Braley’s campaign did not respond to a request for comment.

The Obama administration has indefinitely delayed approval of the pipeline in a move that is widely seen as political. Some Democratic candidates oppose Keystone while others in states with large oil economies support it, but the delay enables the party to mask those divisions for the elections this fall.

The administration’s indecision comes after the State Department’s environmental review of the project found that it would not have a “significant” impact on greenhouse gas emissions. The review also said construction would support about 42,000 jobs over a two-year period.

The National Republican Senatorial Committee (NRSC) previously criticized Braley for not breaking with the administration and advocating for the pipeline.

“Bruce Braley claims to be a moderate, but in Washington he just empowers the liberal Obama/Reid/Schumer/Pelosi anti-energy agenda which costs jobs in Iowa,” said NRSC press secretary Brook Hougesen. “Iowa workers, businesses, and families have been crippled by the liberal agenda of more regulations, higher taxes, and the empowerment of bureaucrats at EPA that has crippled growth and created a mountain of uncertainty.”

The pipeline would carry oil from the tar sands of Alberta, Canada, down to Gulf Coast refineries. It requires approval from the administration because it would cross international borders.

The delay of the pipeline could spell trouble for Braley this fall. Among Iowa general election voters who support the project, 49 percent said they would be less likely to support a Democratic Senate candidate if President Barack Obama denied the permit to build it, according to a survey earlier this month by the Consumer Energy Alliance.

Braley, a former trial lawyer, generated criticism after he called Sen. Chuck Grassley (R., Iowa) a “farmer from Iowa who never went to law school” at a January fundraiser. Many viewed the comments as elitist in the farm-heavy state, and his poll numbers among likely Iowa voters subsequently dropped.

Five Republicans are vying for the nomination to face Braley in the general election. State senator and Iraq War veteran Joni Ernst has opened up a double-digit lead for the June 3 primary, according to a recent poll.

Mark Jacobs, a former Texas energy company CEO who finished second in the poll, criticized Braley in a statement to the Washington Free Beacon.

“Sadly, the policies pursued by this Administration and Rep. Bruce Braley have made growth in the energy sector harder every step of the way,” he said. “We should increase domestic energy production by opening more federal lands and waters to development and fast tracking the permitting process for the infrastructure needed to bring resources safely to market, including the Keystone Pipeline.”

Share

Tweet

BY: Daniel Wiser

May 21, 2014 4:54 pm

Iowa Democratic Senate candidate Bruce Braley reversed his stance on the Keystone XL pipeline last year and is now benefiting from spending by an outside group funded by a billionaire who opposes the project, according to reports.

Braley, a four-term congressman, initially voted in April 2012 to expedite construction of the pipeline. The measure was part of a temporary funding extension for federal transportation projects.

Braley praised the pipeline at the time in a statement: “The pipeline project is an opportunity to create thousands of jobs in Iowa and the Midwest and reduce our dependence on Middle Eastern oil. Environmental concerns must be addressed, and this bill provides an avenue to air those concerns to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission.”

“Keystone XL has attracted rare bipartisan support because of the enormous economic benefits it will provide,” he added. “It should move forward quickly once it’s approved.”

However, Braley voted against construction of the pipeline when a House bill passed last May. He announced his candidacy for the Senate last February.

Recent spending by groups that support Braley has raised questions about whether he switched his position on Keystone to benefit his campaign.

Senate Majority PAC, a Super PAC that aims to maintain a Democratic majority in the Senate and is run by former staffers for Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (D., Nev.), has spent almost $550,000 in support of Braley, according to the Center for Responsive Politics.

The New York Times reported on Saturday that Tom Steyer, a billionaire climate activist and former hedge fund manager, recently contributed $5 million to the Senate Majority PAC—making him the single largest contributor to the Super PAC this year.

Steyer has pledged to spend $100 million ahead of the midterm elections on climate issues, including efforts to block construction of the pipeline. He also has his own Super PAC, NextGen Climate Action.

Steyer is reportedly targeting states such as Florida, Iowa, and Virginia.

“A contribution to Senate Majority PAC, the way they spend it and use it, will be consistent with the criteria that we use to choose our states,” said Chris Lehane, a spokesman for Steyer, in an interview with the Times.

Braley’s campaign did not respond to a request for comment.

The Obama administration has indefinitely delayed approval of the pipeline in a move that is widely seen as political. Some Democratic candidates oppose Keystone while others in states with large oil economies support it, but the delay enables the party to mask those divisions for the elections this fall.

The administration’s indecision comes after the State Department’s environmental review of the project found that it would not have a “significant” impact on greenhouse gas emissions. The review also said construction would support about 42,000 jobs over a two-year period.

The National Republican Senatorial Committee (NRSC) previously criticized Braley for not breaking with the administration and advocating for the pipeline.

“Bruce Braley claims to be a moderate, but in Washington he just empowers the liberal Obama/Reid/Schumer/Pelosi anti-energy agenda which costs jobs in Iowa,” said NRSC press secretary Brook Hougesen. “Iowa workers, businesses, and families have been crippled by the liberal agenda of more regulations, higher taxes, and the empowerment of bureaucrats at EPA that has crippled growth and created a mountain of uncertainty.”

The pipeline would carry oil from the tar sands of Alberta, Canada, down to Gulf Coast refineries. It requires approval from the administration because it would cross international borders.

The delay of the pipeline could spell trouble for Braley this fall. Among Iowa general election voters who support the project, 49 percent said they would be less likely to support a Democratic Senate candidate if President Barack Obama denied the permit to build it, according to a survey earlier this month by the Consumer Energy Alliance.

Braley, a former trial lawyer, generated criticism after he called Sen. Chuck Grassley (R., Iowa) a “farmer from Iowa who never went to law school” at a January fundraiser. Many viewed the comments as elitist in the farm-heavy state, and his poll numbers among likely Iowa voters subsequently dropped.

Five Republicans are vying for the nomination to face Braley in the general election. State senator and Iraq War veteran Joni Ernst has opened up a double-digit lead for the June 3 primary, according to a recent poll.

Mark Jacobs, a former Texas energy company CEO who finished second in the poll, criticized Braley in a statement to the Washington Free Beacon.

“Sadly, the policies pursued by this Administration and Rep. Bruce Braley have made growth in the energy sector harder every step of the way,” he said. “We should increase domestic energy production by opening more federal lands and waters to development and fast tracking the permitting process for the infrastructure needed to bring resources safely to market, including the Keystone Pipeline.”

[h=2]Ellison’s Must Read of the Day[/h]BY: Ellison Barber // May 22, 2014 9:37 am

Share

Tweet

Email

My must read of the day is “Obama is President Passive over the Veterans Affairs scandal,” by Dana Milbank in the Washington Post:

This is horrific. It’s taken too long for the President of the United States to publicly address the situation, and when he did he gave a speech that seemed contrived, offering nothing more than platitudes and talking points.

Surely there are many reasons that could explain this (politics are calculated and that’s what this was, a calculated political response), but Obama seemed appallingly apathetic to the situation, regardless of what he intended. Milbank is right; there are no ifs about this, and no one believes the president is outraged by it, because he can not actually be “madder than hell” if he refuses to concede the basic facts.

Share

Tweet

My must read of the day is “Obama is President Passive over the Veterans Affairs scandal,” by Dana Milbank in the Washington Post:

Over the weekend, the president’s chief of staff assured the public that Obama was “madder than hell” about what happened at the Department of Veterans Affairs, but in person Obama didn’t seem very angry. Like VA Secretary Eric Shinseki, Obama wasn’t entirely convinced something bad had happened. [...]

But there are no “ifs” about it: Numerous inquiries and leaked memos over several years point to “gaming strategies” employed at VA facilities to make wait times for medical appointments seem shorter — and these clearly aren’t limited to those reported in Phoenix; Albuquerque; Fort Collins, Colo.; and elsewhere. Lawmakers in both parties have spoken of a systemic problem at the agency, and the American Legion, citing “poor oversight,” has called for Shinseki’s resignation — the first time it has made such a gesture in more than 70 years.

Obama said Wednesday that he doesn’t want the matter to become “another political football,” and that’s understandable. But his response to the scandal has created an inherent contradiction: He can’t be “madder than hell” about something if he won’t acknowledge that the thing actually occurred. This would be a good time for Obama to knock heads and to get in front of the story. But, frustratingly, he’s playing President Passive, insisting on waiting for the VA’s inspector general to complete yet another investigation, this one looking into the Phoenix deaths.

No one is asking that Obama feign outrage or emote to appease the masses, but why wouldn’t that be his natural reaction?But there are no “ifs” about it: Numerous inquiries and leaked memos over several years point to “gaming strategies” employed at VA facilities to make wait times for medical appointments seem shorter — and these clearly aren’t limited to those reported in Phoenix; Albuquerque; Fort Collins, Colo.; and elsewhere. Lawmakers in both parties have spoken of a systemic problem at the agency, and the American Legion, citing “poor oversight,” has called for Shinseki’s resignation — the first time it has made such a gesture in more than 70 years.

Obama said Wednesday that he doesn’t want the matter to become “another political football,” and that’s understandable. But his response to the scandal has created an inherent contradiction: He can’t be “madder than hell” about something if he won’t acknowledge that the thing actually occurred. This would be a good time for Obama to knock heads and to get in front of the story. But, frustratingly, he’s playing President Passive, insisting on waiting for the VA’s inspector general to complete yet another investigation, this one looking into the Phoenix deaths.

This is horrific. It’s taken too long for the President of the United States to publicly address the situation, and when he did he gave a speech that seemed contrived, offering nothing more than platitudes and talking points.

Surely there are many reasons that could explain this (politics are calculated and that’s what this was, a calculated political response), but Obama seemed appallingly apathetic to the situation, regardless of what he intended. Milbank is right; there are no ifs about this, and no one believes the president is outraged by it, because he can not actually be “madder than hell” if he refuses to concede the basic facts.

Green billionaire prepares to attack 'anti-science' Republicans

http://www.cnn.com/2014/05/22/politics/steyer-climate-change-campaign/

Washington (CNN) -- An environmental advocacy group backed by hedge fund tycoon Tom Steyer is set to unleash a seven-state, $100 million offensive against Republican "science deniers" this year, a no-holds-barred campaign-style push from the green billionaire that could help decide which party controls the Senate and key statehouses come November.

"They are anti-immigrant, anti-women, anti-science," he said. "It's a tough brand to win elections around."

http://www.cnn.com/2014/05/22/politics/steyer-climate-change-campaign/

Washington (CNN) -- An environmental advocacy group backed by hedge fund tycoon Tom Steyer is set to unleash a seven-state, $100 million offensive against Republican "science deniers" this year, a no-holds-barred campaign-style push from the green billionaire that could help decide which party controls the Senate and key statehouses come November.

"They are anti-immigrant, anti-women, anti-science," he said. "It's a tough brand to win elections around."

[h=2]First Nation Official Lauds Koch Engagement with Canadian Tribe[/h]Share

Tweet

Email

Oil sands in Alberta, Canada / AP

Oil sands in Alberta, Canada / AP

BY: Washington Free Beacon Staff

May 27, 2014 10:53 am

A subsidiary of Koch Industries has been proactive and productive in its talks with a tribal government near the site of a new oil extraction project in Canada, a tribal leader told the Toronto Globe and Mail on Tuesday.

Koch Oil Sands Operating LLC announced plans to develop a multi-billion-dollar oil sands project in Alberta, Canada, the Globe and Mail reported. The proposed project is near the Fort McKay First Nation.

Koch has been attentive to tribal concerns and has made an effort to reach out to representatives of the First Nation government, Fort McKay regulatory and environmental manager Dan Stuckless said.

“They came to us quite early in the process compared to most these days,” Stuckless told the Globe and Mail. According to the report, Stuckless felt “discussions have shown a desire by the developer to learn about Fort McKay and its priorities.”

Tweet

BY: Washington Free Beacon Staff

May 27, 2014 10:53 am

A subsidiary of Koch Industries has been proactive and productive in its talks with a tribal government near the site of a new oil extraction project in Canada, a tribal leader told the Toronto Globe and Mail on Tuesday.

Koch Oil Sands Operating LLC announced plans to develop a multi-billion-dollar oil sands project in Alberta, Canada, the Globe and Mail reported. The proposed project is near the Fort McKay First Nation.

Koch has been attentive to tribal concerns and has made an effort to reach out to representatives of the First Nation government, Fort McKay regulatory and environmental manager Dan Stuckless said.

“They came to us quite early in the process compared to most these days,” Stuckless told the Globe and Mail. According to the report, Stuckless felt “discussions have shown a desire by the developer to learn about Fort McKay and its priorities.”

[h=2]Tom Steyer Remains Invested in Fossil Fuels Despite Divestment Pledge[/h]One of five key takeaways from Washington Post profile on billionaire environmentalist

Share

Tweet

Email

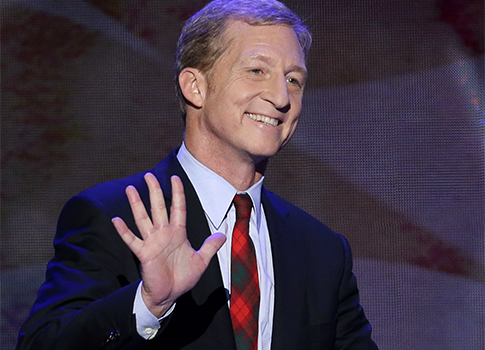

Tom Steyer / AP

Tom Steyer / AP

BY: Lachlan Markay

June 9, 2014 1:00 pm

The Washington Post on Monday published a profile of billionaire hedge fund manager Tom Steyer that explored his transition from investor in massive fossil fuel projects to politically potent environmentalist.

The story offers previously unreported details on Steyer’s sizable investments through Farallon Capital—the hedge fund he founded and ran for more than 25 years—in coal power and other carbon-intensive projects.

As Steyer has pushed an agenda driven primarily by opposition to the popular Keystone XL pipeline, which would carry “oil sands” crude from northwestern Canada to refineries and export terminals on the Gulf coast, critics have pointed out that Farallon’s energy investments swelled global carbon emissions far more than Keystone, or any oil pipeline project, likely will.

The Post story on that disconnect reveals five key takeaways.

[h=3]1. Steyer is still invested in fossil fuels.

[/h] AP

AP

Steyer spokeswoman Heather Wong told the Post that he had directed Farallon to divest his holdings from all coal and oil sands projects last year. She said that his portfolio “will be free of all fossil-fuel firms,” including all oil and natural gas companies, “by the end of this month.”

Neither Steyer nor his staff would provide the Post with documentation detailing the new guidelines for his Farallon portfolio.

If Wong’s characterization is accurate, Steyer is still profiting off of fossil fuel activity that many environmentalists, including the man who recruited Steyer into the movement and acts as his political adviser, insist is worsening global climate change.

[h=3]2. Steyer was recruited and is still advised by one of the country’s most radical environmentalists.[/h] Bill McKibben / AP

Bill McKibben / AP

The Post reports that Steyer’s foray into the U.S. political arena began during an Adirondack hike with Middlebury University professor and environmental activist Bill McKibben.

McKibben is one of the country’s leading critics of hydraulic fracturing, an innovative oil and gas extraction technique that has unlocked massive reserves of carbon-based energy and economically revitalized areas of the country that sit above large shale formations.

Like Steyer, McKibben vehemently opposes the Keystone pipeline. However, unlike many on the left, including leading Obama administration regulators, he has suggested that fracking should be banned outright.

McKibben and other anti-fracking environmentalists say the relatively low emissions of natural gas-fired power is negated by methane emissions at the site of gas extraction. McKibben says the practice is “a huge worry for global warming reasons.”

That claim relies on a handful of studies that have found high “fugitive” methane leaks at fracking sites. Most studies, including those on which Obama’s Environmental Protection Agency has based its position, have found that fracked natural gas produces significantly fewer emissions than coal power.

At the onset of his political crusade, Steyer signaled that he would be more amenable to fracked natural gas as a “bridge fuel” that could supply the power necessary to reduce disruptions from a total phase-out of coal, since renewables such as wind and solar cannot make up that shortfall.

Steyer even helped finance a University of Texas study that supported that position.

However, he has signaled more recently that he is closer to McKibben’s position on the issue. Steyer lieutenant Chris Lehane recently suggested that NextGen Climate Action, his political group, may push an anti-fracking message in Colorado, where Rep. Jared Polis (D., Colo.), has said he will use his personal fortune to push for anti-fracking measures on the ballot in November.

[h=3]3. Steyer’s divestment from natural gas suggests he sees it as part of the problem[/h] New natural gas burning plant in Kentucky / AP

New natural gas burning plant in Kentucky / AP

To the extent that Steyer’s position on fracking is ambiguous, his new portfolio approach at Farallon offers some insight.

“Tom publicly identified coal and tar sands as those are the fossil fuels that are having a specific impact on climate and where the battle for our kids is being fought — he then expanded his divestment at the beginning of this year because he felt it was simply the right thing to do,” Wong told the Post.

Those expanded divestment orders include natural gas companies, Wong said, suggesting that he sees the fuel as part of the problem, not simply as a “bridge fuel” to help wean the nation off of coal-fired power.

[h=3]4. Steyer’s Keystone opposition is largely symbolic[/h] AP

AP

“I think he understood the logic of the Keystone fight right away — that it was crucial in its own right and also a way to draw a line in the sand,” McKibben told the Post.

According to the U.S. State Department, the Obama administration’s decision on the Keystone pipeline will have a negligible impact on carbon emissions—let alone global climate—since the oil will be extracted, exported, refined, and burned whether or not the pipeline is built.

McKibben sees opposition to the project as a cause around which a demoralized environmentalist movement can rally, and his success in blocking it is as much about scoring a political victory as it is about helping the planet.

Steyer is apparently of the same mind.

[h=3]5. Steyer said environmentalist anger at Farallon was a wake-up call, but he continued investing in carbon-intensive fuels[/h] Tom Steyer / AP

Tom Steyer / AP

Ten years ago a number of students at Yale University, Steyer’s alma mater, and other colleges protested university endowments that included stakes in Farallon and demanded that their schools divest from those holdings.

The students targeted Farallon for its extensive investments in coal and other carbon-intensive fuels, and for what they described as illegal or socially irresponsible investment practices by the hedge fund.

“The protests embarrassed Steyer and his wife, Kat Taylor, who were major donors to Democratic causes,” the Post reported. “They began to wonder if, and when, they might bring their business interests in line with their values.”

However, Farallon continued investing in the types of projects to which the students had objected. By the time Steyer hiked with McKibben, “Farallon, still led at the time by Steyer, had just invested in a company seeking to extract oil” crude from Canadian oil sands, the Post noted.

Share

Tweet

BY: Lachlan Markay

June 9, 2014 1:00 pm

The Washington Post on Monday published a profile of billionaire hedge fund manager Tom Steyer that explored his transition from investor in massive fossil fuel projects to politically potent environmentalist.

The story offers previously unreported details on Steyer’s sizable investments through Farallon Capital—the hedge fund he founded and ran for more than 25 years—in coal power and other carbon-intensive projects.

As Steyer has pushed an agenda driven primarily by opposition to the popular Keystone XL pipeline, which would carry “oil sands” crude from northwestern Canada to refineries and export terminals on the Gulf coast, critics have pointed out that Farallon’s energy investments swelled global carbon emissions far more than Keystone, or any oil pipeline project, likely will.

The Post story on that disconnect reveals five key takeaways.

[h=3]1. Steyer is still invested in fossil fuels.

[/h]

Steyer spokeswoman Heather Wong told the Post that he had directed Farallon to divest his holdings from all coal and oil sands projects last year. She said that his portfolio “will be free of all fossil-fuel firms,” including all oil and natural gas companies, “by the end of this month.”

Neither Steyer nor his staff would provide the Post with documentation detailing the new guidelines for his Farallon portfolio.

If Wong’s characterization is accurate, Steyer is still profiting off of fossil fuel activity that many environmentalists, including the man who recruited Steyer into the movement and acts as his political adviser, insist is worsening global climate change.

[h=3]2. Steyer was recruited and is still advised by one of the country’s most radical environmentalists.[/h]

The Post reports that Steyer’s foray into the U.S. political arena began during an Adirondack hike with Middlebury University professor and environmental activist Bill McKibben.

McKibben is one of the country’s leading critics of hydraulic fracturing, an innovative oil and gas extraction technique that has unlocked massive reserves of carbon-based energy and economically revitalized areas of the country that sit above large shale formations.

Like Steyer, McKibben vehemently opposes the Keystone pipeline. However, unlike many on the left, including leading Obama administration regulators, he has suggested that fracking should be banned outright.

McKibben and other anti-fracking environmentalists say the relatively low emissions of natural gas-fired power is negated by methane emissions at the site of gas extraction. McKibben says the practice is “a huge worry for global warming reasons.”

That claim relies on a handful of studies that have found high “fugitive” methane leaks at fracking sites. Most studies, including those on which Obama’s Environmental Protection Agency has based its position, have found that fracked natural gas produces significantly fewer emissions than coal power.

At the onset of his political crusade, Steyer signaled that he would be more amenable to fracked natural gas as a “bridge fuel” that could supply the power necessary to reduce disruptions from a total phase-out of coal, since renewables such as wind and solar cannot make up that shortfall.

Steyer even helped finance a University of Texas study that supported that position.

However, he has signaled more recently that he is closer to McKibben’s position on the issue. Steyer lieutenant Chris Lehane recently suggested that NextGen Climate Action, his political group, may push an anti-fracking message in Colorado, where Rep. Jared Polis (D., Colo.), has said he will use his personal fortune to push for anti-fracking measures on the ballot in November.

[h=3]3. Steyer’s divestment from natural gas suggests he sees it as part of the problem[/h]

To the extent that Steyer’s position on fracking is ambiguous, his new portfolio approach at Farallon offers some insight.

“Tom publicly identified coal and tar sands as those are the fossil fuels that are having a specific impact on climate and where the battle for our kids is being fought — he then expanded his divestment at the beginning of this year because he felt it was simply the right thing to do,” Wong told the Post.

Those expanded divestment orders include natural gas companies, Wong said, suggesting that he sees the fuel as part of the problem, not simply as a “bridge fuel” to help wean the nation off of coal-fired power.

[h=3]4. Steyer’s Keystone opposition is largely symbolic[/h]

“I think he understood the logic of the Keystone fight right away — that it was crucial in its own right and also a way to draw a line in the sand,” McKibben told the Post.

According to the U.S. State Department, the Obama administration’s decision on the Keystone pipeline will have a negligible impact on carbon emissions—let alone global climate—since the oil will be extracted, exported, refined, and burned whether or not the pipeline is built.

McKibben sees opposition to the project as a cause around which a demoralized environmentalist movement can rally, and his success in blocking it is as much about scoring a political victory as it is about helping the planet.

Steyer is apparently of the same mind.

[h=3]5. Steyer said environmentalist anger at Farallon was a wake-up call, but he continued investing in carbon-intensive fuels[/h]

Ten years ago a number of students at Yale University, Steyer’s alma mater, and other colleges protested university endowments that included stakes in Farallon and demanded that their schools divest from those holdings.

The students targeted Farallon for its extensive investments in coal and other carbon-intensive fuels, and for what they described as illegal or socially irresponsible investment practices by the hedge fund.

“The protests embarrassed Steyer and his wife, Kat Taylor, who were major donors to Democratic causes,” the Post reported. “They began to wonder if, and when, they might bring their business interests in line with their values.”

However, Farallon continued investing in the types of projects to which the students had objected. By the time Steyer hiked with McKibben, “Farallon, still led at the time by Steyer, had just invested in a company seeking to extract oil” crude from Canadian oil sands, the Post noted.

[h=2]Tom Steyer: Party Animal[/h]$5 million donation suggests Steyer is a Democrat before he’s an environmentalist

Share

Tweet

Email

Tom Steyer / AP

Tom Steyer / AP

BY: Lachlan Markay

June 13, 2014 10:04 am

Billionaire environmentalist Tom Steyer poured another $7.1 million into his political group during the second quarter of this year, new documents show, the bulk of which was then passed on to a leading Democratic group.

The documents show that Steyer is looking to influence more U.S. Senate races than those specifically targeted by his group, and that he is less ideologically constrained to environmentalist candidates than previously believed.

On April 21, Steyer wrote NextGen Climate Action, his independent expenditure committee, a $5 million check specifically “earmarked for Senate Majority PAC,” a Democratic group with deep ties to Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (D., Nev.).

Nine days later, Federal Election Commission records show, NextGen passed along a “conduit contribution” of the same sum to Senate Majority PAC.

The contribution dwarfed independent expenditures by NextGen itself during the first six months of the year. The FEC records list less than $150,000 in such expenditures through the end of May.

Those expenditures bought digital advertising opposing Republican Senate candidates in Colorado, Iowa, Michigan, and New Hampshire, the four races that Steyer announced as NextGen targets in May.

Though NextGen is confining its work on U.S. Senate races to those four states, its support for Senate Majority PAC, which is involved in nearly every competitive Senate race around the country, shows that Steyer plans to influence elections beyond those specifically designated as NextGen targets.

In addition to NextGen’s target states, Senate Majority PAC has hit Republicans candidates or incumbents, directly or through front groups, in Arkansas, Louisiana, Montana, Alaska, North Carolina, Colorado, and Kentucky.

As Steyer signaled more involvement in Senate races earlier this year, Democrats worried that his strident environmentalist views could cost Democrats their majority.

Steyer’s group even suggested that it might go on offense against Sen. Mary Landrieu (D., La.) due to her support for the Keystone XL pipeline, which Steyer vehemently opposes.

“I say over and over, ‘Lord protect me from my friends so I can focus on my enemies,’” one Democratic strategist supporting Landrieu told National Journal. “This is an apparent case of that.”

Steyer’s support for Senate Majority PAC suggests that those fears were unfounded.

Steyer is indirectly supporting Landrieu, as well as candidates such as Kentucky Democrat Alison Lundergan Grimes, who is an outspoken supporter of her state’s coal industry, through his $5 million contribution to Senate Majority PAC.

“I don’t think his underlying feelings have changed. But I think he realizes certain things are just not possible,” one source familiar with Steyer’s political activity told Reuters.

Steyer may have recognized the value of a Democratic Senate majority to his environmentalist goals. But that now entails supporting Democrats who do not always share those goals.

Share

Tweet

BY: Lachlan Markay

June 13, 2014 10:04 am

Billionaire environmentalist Tom Steyer poured another $7.1 million into his political group during the second quarter of this year, new documents show, the bulk of which was then passed on to a leading Democratic group.

The documents show that Steyer is looking to influence more U.S. Senate races than those specifically targeted by his group, and that he is less ideologically constrained to environmentalist candidates than previously believed.

On April 21, Steyer wrote NextGen Climate Action, his independent expenditure committee, a $5 million check specifically “earmarked for Senate Majority PAC,” a Democratic group with deep ties to Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (D., Nev.).

Nine days later, Federal Election Commission records show, NextGen passed along a “conduit contribution” of the same sum to Senate Majority PAC.

The contribution dwarfed independent expenditures by NextGen itself during the first six months of the year. The FEC records list less than $150,000 in such expenditures through the end of May.

Those expenditures bought digital advertising opposing Republican Senate candidates in Colorado, Iowa, Michigan, and New Hampshire, the four races that Steyer announced as NextGen targets in May.

Though NextGen is confining its work on U.S. Senate races to those four states, its support for Senate Majority PAC, which is involved in nearly every competitive Senate race around the country, shows that Steyer plans to influence elections beyond those specifically designated as NextGen targets.

In addition to NextGen’s target states, Senate Majority PAC has hit Republicans candidates or incumbents, directly or through front groups, in Arkansas, Louisiana, Montana, Alaska, North Carolina, Colorado, and Kentucky.

As Steyer signaled more involvement in Senate races earlier this year, Democrats worried that his strident environmentalist views could cost Democrats their majority.

Steyer’s group even suggested that it might go on offense against Sen. Mary Landrieu (D., La.) due to her support for the Keystone XL pipeline, which Steyer vehemently opposes.

“I say over and over, ‘Lord protect me from my friends so I can focus on my enemies,’” one Democratic strategist supporting Landrieu told National Journal. “This is an apparent case of that.”

Steyer’s support for Senate Majority PAC suggests that those fears were unfounded.

Steyer is indirectly supporting Landrieu, as well as candidates such as Kentucky Democrat Alison Lundergan Grimes, who is an outspoken supporter of her state’s coal industry, through his $5 million contribution to Senate Majority PAC.

“I don’t think his underlying feelings have changed. But I think he realizes certain things are just not possible,” one source familiar with Steyer’s political activity told Reuters.

Steyer may have recognized the value of a Democratic Senate majority to his environmentalist goals. But that now entails supporting Democrats who do not always share those goals.

[h=2]Open Access[/h]White House Opens Doors for Billionaire Donor Tom Steyer

Share

Tweet

Email

Tom Steyer / AP

Tom Steyer / AP

BY: Reuters

June 25, 2014 10:21 am

(Reuters) – White House officials and Treasury Secretary Jack Lew will meet with billionaire environmental activist Tom Steyer on Wednesday to discuss climate change, a White House official said.

The meeting will include former Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson, former Secretary of Housing and Urban Development Henry Cisneros, and Cargill Chief Executive Greg Page, who have worked together on a forthcoming “Risky Business report,” which studies the economic consequences of climate change.

That report and President Barack Obama’s climate change policies will be the focus of the meeting, the official said.

Steyer is a major opponent of the Keystone XL oil pipeline project. The Obama administration is in the middle of a long process to decide whether to approve or reject the pipeline, which would bring oil from Canada to the Gulf Coast.

Steyer has pledged to spend up to $100 million to make sure climate change is a top issue in the November U.S. elections. His meeting with White House officials illustrates the extent to which the administration wants his support, and the increasing importance Steyer has placed on working with, not against, members of the Democratic Party.

The meeting is part of a White House push on climate change policy. Earlier this month, the Obama administration unveiled new rules limiting carbon dioxide emissions from power plants.

The official said the White House would also host a meeting on Tuesday between administration officials, including senior Obama advisers John Podesta and Valerie Jarrett, and representatives from insurance and re-insurance companies to “discuss the economic consequences of increasingly frequent and severe extreme weather and the insurance industry’s role in helping American communities prepare for extreme weather and other impacts of climate change.”

(Reporting by Jeff Mason; Editing by Mohammad Zargham)

Share

Tweet

BY: Reuters

June 25, 2014 10:21 am

(Reuters) – White House officials and Treasury Secretary Jack Lew will meet with billionaire environmental activist Tom Steyer on Wednesday to discuss climate change, a White House official said.

The meeting will include former Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson, former Secretary of Housing and Urban Development Henry Cisneros, and Cargill Chief Executive Greg Page, who have worked together on a forthcoming “Risky Business report,” which studies the economic consequences of climate change.

That report and President Barack Obama’s climate change policies will be the focus of the meeting, the official said.

Steyer is a major opponent of the Keystone XL oil pipeline project. The Obama administration is in the middle of a long process to decide whether to approve or reject the pipeline, which would bring oil from Canada to the Gulf Coast.

Steyer has pledged to spend up to $100 million to make sure climate change is a top issue in the November U.S. elections. His meeting with White House officials illustrates the extent to which the administration wants his support, and the increasing importance Steyer has placed on working with, not against, members of the Democratic Party.

The meeting is part of a White House push on climate change policy. Earlier this month, the Obama administration unveiled new rules limiting carbon dioxide emissions from power plants.

The official said the White House would also host a meeting on Tuesday between administration officials, including senior Obama advisers John Podesta and Valerie Jarrett, and representatives from insurance and re-insurance companies to “discuss the economic consequences of increasingly frequent and severe extreme weather and the insurance industry’s role in helping American communities prepare for extreme weather and other impacts of climate change.”

(Reporting by Jeff Mason; Editing by Mohammad Zargham)

[h=2]Network Coverage of Kochs Dwarfs Attention to Steyer, Soros[/h]Share

Tweet

Email

George Soros / AP

George Soros / AP

BY: Washington Free Beacon Staff

June 24, 2014 5:04 pm

The three network news channels have devoted nine times more coverage to the political activities of Charles and David Koch than those of Tom Steyer and George Soros, Fox News reported on Tuesday.

Media Research Center vice president Dan Gainor said the discrepancy demonstrates that “ABC, CBS and NBC have set ethics aside and joined a liberal crusade to demonize conservative billionaires David and Charles Koch.”

Tweet

BY: Washington Free Beacon Staff

June 24, 2014 5:04 pm

The three network news channels have devoted nine times more coverage to the political activities of Charles and David Koch than those of Tom Steyer and George Soros, Fox News reported on Tuesday.

Media Research Center vice president Dan Gainor said the discrepancy demonstrates that “ABC, CBS and NBC have set ethics aside and joined a liberal crusade to demonize conservative billionaires David and Charles Koch.”

ABC, CBS and NBC have entirely ignored big-monied liberal organizations like the Democracy Alliance, which is spending $200 million to “to boost liberal candidates and causes.” Even on June 23, when Politico reported on a secretive April Democracy Alliance meeting, there was no coverage.

Broadcast journalists have had it in for the Koch brothers. Their contributions, we’re told, have funded “very, very conservative causes,” they operate in “secrecy” and are part of the “elite.” One ABC story featured representatives from three separate George-Soros-funded organizations to criticize the Kochs. Not one of them was identified as such.

To journalists, only conservative money is ever suspect. Those neutral network types even dug up professional left-wingers like “Colbert Report” host Stephen Colbert and ultra-liberal Chris Matthews, of MSNBC, to whine about conservative money

Broadcast journalists have had it in for the Koch brothers. Their contributions, we’re told, have funded “very, very conservative causes,” they operate in “secrecy” and are part of the “elite.” One ABC story featured representatives from three separate George-Soros-funded organizations to criticize the Kochs. Not one of them was identified as such.

To journalists, only conservative money is ever suspect. Those neutral network types even dug up professional left-wingers like “Colbert Report” host Stephen Colbert and ultra-liberal Chris Matthews, of MSNBC, to whine about conservative money

[h=2]Billionaire Tom Steyer Recycling False Attacks in Iowa[/h]$2.6 million spent on false attack ad targeting Joni Ernst

Share

Tweet

Email

Tom Steyer / AP

Tom Steyer / AP

BY: Washington Free Beacon Staff

July 30, 2014 3:13 pm

Liberal billionaire Tom Steyer is running an attack ad against Iowa Republican Senate candidate Joni Ernst regarding her pledge not to raise taxes, but the ad uses recycled attacks that have already been debunked in previous elections, according to Americans for Tax Reform.

The ad is part of a $2.6 million ad buy made by Steyer’s NextGen Climate to combat Ernst in Iowa.

The attacks in the ad have been used in the past against other candidates that have signed on to the pledge against hiking taxes, and multiple fact checks have found the claims made to be false.

For example, the ad ties Ernst’s pledge to outsourcing. FactCheck.org concluded that this was not the case in 2010 when the attack was used by Virginia Democrat Tom Perriello in a race he would end up losing to Republican Robert Hurt:

This entry was posted in Politics and tagged 2014 Elections, Democratic Donors, Joni Ernst, Tom Steyer. Bookmark the permalink.

Share

Tweet

BY: Washington Free Beacon Staff

July 30, 2014 3:13 pm

Liberal billionaire Tom Steyer is running an attack ad against Iowa Republican Senate candidate Joni Ernst regarding her pledge not to raise taxes, but the ad uses recycled attacks that have already been debunked in previous elections, according to Americans for Tax Reform.

The ad is part of a $2.6 million ad buy made by Steyer’s NextGen Climate to combat Ernst in Iowa.

The attacks in the ad have been used in the past against other candidates that have signed on to the pledge against hiking taxes, and multiple fact checks have found the claims made to be false.

For example, the ad ties Ernst’s pledge to outsourcing. FactCheck.org concluded that this was not the case in 2010 when the attack was used by Virginia Democrat Tom Perriello in a race he would end up losing to Republican Robert Hurt:

But the fact that someone signed the pledge doesn’t necessarily mean they are opposed to closing loopholes for off-shore companies.

Our friends at FactCheck.org have been knocking down this claim since April, when the DCCC ran a TV ad against a Republican House candidate in Hawaii. They recently debunked the same claim in an ad in the Massachusetts gubernatorial campaign.

Here’s the problem: The taxpayer pledge doesn’t prevent a signer from opposing any tax break as long as he or she finds a way to offset the resulting increase in taxes.

[The attack is] a huge leap of logic and it doesn’t prove Hurt supports the offshore loopholes. So we find the claim False.

“Tom Steyer needs to find honest and original consultants,” said Grover Norquist, president of Americans for Tax Reform. “The plagiarized attack ads he’s running have already been proven false by several fact checkers four years ago, in 2010. Rather than attacking Joni Ernst, he should be praising her for her principled stand against higher taxes. Taxpayers in Iowa are looking for someone to stand up to the special interests in Washington and she is exactly the candidate to do that. Steyer deserves a refund from those who cheated him”Our friends at FactCheck.org have been knocking down this claim since April, when the DCCC ran a TV ad against a Republican House candidate in Hawaii. They recently debunked the same claim in an ad in the Massachusetts gubernatorial campaign.

Here’s the problem: The taxpayer pledge doesn’t prevent a signer from opposing any tax break as long as he or she finds a way to offset the resulting increase in taxes.

[The attack is] a huge leap of logic and it doesn’t prove Hurt supports the offshore loopholes. So we find the claim False.

This entry was posted in Politics and tagged 2014 Elections, Democratic Donors, Joni Ernst, Tom Steyer. Bookmark the permalink.

[h=2]Steyer Visited Podesta at WH Days After Pledging $100M for Dems[/h]Share

Tweet

Email

Tom Steyer / Wikimedia Commons

Tom Steyer / Wikimedia Commons

BY: Washington Free Beacon Staff

August 6, 2014 9:22 am

Billionaire environmentalist Tom Steyer met with White House climate adviser John Podesta just days after Steyer announced he would raise $100 million to elect Democrats during the 2014 election cycle.

Also attending the meeting, according to White House visitor logs, were liberal billionaire George Soros and Michael Vachon, a top Soros lieutenant.

“They discussed a variety of topics,” Vachon told E&E News. He declined to elaborate.

Both Steyer and Soros are also involved with the shadowy left wing donor network the Democracy Alliance, which has steered large sums to CAP, one of its top dark money beneficiaries.

The meeting marked Steyer’s twelfth visit to the Obama White House, Politico reported.

Tweet

BY: Washington Free Beacon Staff

August 6, 2014 9:22 am

Billionaire environmentalist Tom Steyer met with White House climate adviser John Podesta just days after Steyer announced he would raise $100 million to elect Democrats during the 2014 election cycle.

Also attending the meeting, according to White House visitor logs, were liberal billionaire George Soros and Michael Vachon, a top Soros lieutenant.

“They discussed a variety of topics,” Vachon told E&E News. He declined to elaborate.

Opposing the Keystone XL pipeline has been one of the key pillars of Steyer’s environmental agenda, and that issue may also have arisen at the meeting with Podesta, a longtime critic of Canadian oil sands development. However, Podesta said when he joined Obama’s staff that he would steer clear of that decision.

The White House would not comment on the content of the meeting, and it’s unclear whether specifics of Steyer’s campaign or the pipeline were discussed.

While federal law prohibits most federal employees from engaging in some political activities while on the job, as a top member of Obama’s staff, “Podesta’s at a level where he is allowed to engage in political activity while on duty,” said Scott Coffina, former associate counsel to President George W. Bush. “In terms of having a meeting to discuss political strategy and partisan political strategy, that’s OK.”

Prior to his stint at the White House, Podesta was the president of the Center for American Progress, a Democratic messaging outfit on whose board Steyer sits, and to which Soros has donated large, undisclosed sums.The White House would not comment on the content of the meeting, and it’s unclear whether specifics of Steyer’s campaign or the pipeline were discussed.

While federal law prohibits most federal employees from engaging in some political activities while on the job, as a top member of Obama’s staff, “Podesta’s at a level where he is allowed to engage in political activity while on duty,” said Scott Coffina, former associate counsel to President George W. Bush. “In terms of having a meeting to discuss political strategy and partisan political strategy, that’s OK.”

Both Steyer and Soros are also involved with the shadowy left wing donor network the Democracy Alliance, which has steered large sums to CAP, one of its top dark money beneficiaries.

The meeting marked Steyer’s twelfth visit to the Obama White House, Politico reported.

"

"