You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Netanyahu and Putin cozy up to one another (Israel has no choice because a Muslim is occupying the White House)

- Thread starter SheriffJoe

- Start date

Keep on spouting the RT and TASS line, and drinking the Stolichnaya.

What's wrong with growing a beard. Many religious people in my neighborhood have them.Are you going full on anti Semite also in your descent?

“What hairdressers do today, shaving and trimming men’s beards, is an accessory to sin,” reads the leaflet, which quotes a selection of hadiths, or sayings of the Prophet Mohammed, supporting the claim that he banned shaving.

“Thanks to our brothers from the Islamic police, an order has been issued for the shaving of beards to be banned and violators to be detained,” it says.

My G-d, another RT propaganda piece. https://www.rt.com/news/324207-churkin-un-oil-isis-turkey/ How pitiful.Obama sat and watched as ISIS transported and moved its oil freely for over a year. Until Putin showed the world what was going on. Obamas drones followed the thousands of tankers driven by ISIS cross Turkey border and to their destination, followed them to the points which they offloaded their oil.

But Obama silence, deafening silence. Obama turned a blind eye to the real enemy Turkey. Obama loves America's enemies.

Russia fills the void and carries the Oil baton.

While Obama sleeps

Russia wants to stop ISIS’ illegal oil trade – Churkin

Russia is working with the UN Security Council on a document that would enforce stricter implementation of Resolution 2199, which aims to curb illegal oil trade with and by terrorist groups, Russian ambassador to the UN Vitaly Churkin told RIA Novosti.

The draft resolution intends to quash the financing of terrorist groups, including Islamic State (IS, formerly ISIS/ISIL) extremists.

“We are not happy with the way Resolution 2199, which was our initiative, is controlled and implemented. We want to toughen the whole procedure,” Churkin said. “We are already discussing the text with some colleagues and I must say that so far there is not a lot of contention being expressed.”

The new document is a follow-up to Russian-sponsored Resolution 2199, which was adopted by the UN on February 12 to put a stop to illicit oil deals with terrorist structures using the UN Security Council’s sanctions toolkit.

More specifically, it bans all types of oil trade with IS and Jabhat al-Nusra. If such transactions are discovered, they are labeled as financial aid to terrorists and result in targeted sanctions being imposed by the Security Council against participating individuals or companies.

Back in July, the UN Security Council expressed “grave concern” over reports of oil trading with IS militant groups in Iraq and Syria. The statement came after IS seized control of oilfields in the area and was reportedly using the revenues to finance its nascent “state.”

‘Erdogan supporting ISIS, black oil market’ – retired US army general

While Ambassador Churkin has proposed sanctioning states trading with IS terrorists, a retired US army general, believes that Churkin should be more specific in identifying the state actors involved in the illegal oil trade.

Retired US Army Major General Paul E. Vallely, who has recently been lobbying for the Syrian rebels to cooperate with Russia against Islamic State, as well as for Washington to take a more active role in the war on IS, says Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan should be singled out as a “negative force” for supporting Islamic State’s black market oil revenues.

My G-d, another RT propaganda piece. https://www.rt.com/news/324207-churkin-un-oil-isis-turkey/ How pitiful.

Obama Spares ISIS Oil Facilities to Save the Earth

By Daniel John Sobieski

One may be thankful that President Harry S. Truman didn’t have to file an environmental impact statement before he dropped the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, acts which shortened and won World War II and saved hundreds of thousands of lives.

If you wondered why our air campaign against ISIS was inept, consider the statement by Mike Morell, speaking on the “Charlie Rose” program Tuesday night that we didn’t take out the oil facilities that ISIS was using to become the best financed terrorist organization in history because of our concern the environment would be harmed. As the Washington Times reported:

A former CIA director said the U.S.-led coalition fighting the Islamic State has been reluctant to attack oil wells controlled by the extremist group partly because of environmental concerns.

We didn’t go after oil wells -- actually hitting oil wells that ISIS controls because we didn’t want to do environmental damage, and we didn’t want to destroy that infrastructure,” said former spy chief Michael Morell, using an acronym for the Islamic State.

So much for the campaign to “degrade and destroy” ISIS, giving credence to the adage that there is no specific and credible evidence of intelligence in the White House. You win wars by breaking things and killing the enemy and letting the sea levels take care of themselves. You don’t win by worrying that destroying an enemy’s infrastructure might melt a glacier in a hundred years.We didn’t go after oil wells -- actually hitting oil wells that ISIS controls because we didn’t want to do environmental damage, and we didn’t want to destroy that infrastructure,” said former spy chief Michael Morell, using an acronym for the Islamic State.

Our delusional president has embraced the line that climate change is our greatest national security threat and perhaps even the line that global warming has affected the Middle East’s climate to the point where ISIS was moved to behead, rape, and make war on their neighbors. ISIS, President Obama believes that ISIS is a direct response to our carbon footprint.

President Obama, who refused to march with otherworld leaders in Paris after the Charlie Hebdo attack earlier this year, no doubt shook ISIS to its foundation when the President declared, The Hill reports, after the most recent Paris attacks:

“Next week, I will be joining President Hollande and world leaders in Paris for the global climate conference,” Obama said during his prepared remarks, which focused mostly on the efforts to fight the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS).

“What a powerful rebuke to the terrorists it will be, when the world stands as one and shows that we will not be deterred from building a better future for our children,” he added.

What? Does he seriously believe that participating in a gabfest the goal of which is to do great damage to our economy to reduce global temperatures by an immeasurable fraction is a defeat for ISIS. They are laughing all the way to the explosive vest factory -- and the bank they put their oil revenues in.“What a powerful rebuke to the terrorists it will be, when the world stands as one and shows that we will not be deterred from building a better future for our children,” he added.

How much fossil fuel will Air Force One consume as he journeys to the climate confab and back? The Washington Timesrecently noted the environmental cost of President Obama’s April 21, 2015 Earth Day trip:

Earth Day could be interesting in Florida: President Obama will journey aboard Air Force to visit the Everglades on Wednesday, burning jet fuel and taxpayer funds as he goes. Well, at least it’s not as far as Tokyo, which was his Earth Day destination last year. That venture prompted the London Daily Mail to do the math and reveal that magnificent but pricey aircraft consumes 5 gallons of jet fuel for every mile it flies -- emitting over 21 pounds of dreaded CO2 per gallon. The fuel alone costs taxpayers about $180,000 per hour of flight time. Oh, the carbon footprint -- and the irony.

President Obama wants to use the environment to degrade and destroy the U.S. economy based on ideology and not science – much pain for no gain. As Investor’s Business Daily noted:

As Patrick J. Michaels of the Cato Institute noted in a National Review article, "The EPA's own model, ironically acronymed MAGICC, estimates that its new policies will prevent a grand total of 0.018 degrees Celsius in warming by 2100... In fact, dropping the carbon dioxide emissions from all sources of electrical generation to zero would reduce warming by a grand total of 0.04 degrees Celsius by 2100."

That is an amount too small to either measure or sacrifice our economic growth for -- even if the president's policies achieve it.

For this almost imaginary gain, much pain will be inflicted. A Heritage Foundation study predicts U.S. manufacturing job losses totaling 586,000 in just the first seven years of the Clean Power Plan. States with large manufacturing bases and heavy reliance on coal, such as Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio and Wisconsin, would each lose at least 20,000 jobs.

The Heritage study projects that the plan will also result in "a loss of more than $2.5 trillion (inflation-adjusted) in aggregate gross domestic product and a total income loss of more than $7,000 (inflation-adjusted) per person." Put that lump of coal in your stocking.

President Obama would destroy the American economy to fight the mythical threat of climate change but protected the oil wealth of the very real and very deadly threat of ISIS because destroying it might hurt the environment. Go to your climate conference, Mr. President. That’ll show themThat is an amount too small to either measure or sacrifice our economic growth for -- even if the president's policies achieve it.

For this almost imaginary gain, much pain will be inflicted. A Heritage Foundation study predicts U.S. manufacturing job losses totaling 586,000 in just the first seven years of the Clean Power Plan. States with large manufacturing bases and heavy reliance on coal, such as Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio and Wisconsin, would each lose at least 20,000 jobs.

The Heritage study projects that the plan will also result in "a loss of more than $2.5 trillion (inflation-adjusted) in aggregate gross domestic product and a total income loss of more than $7,000 (inflation-adjusted) per person." Put that lump of coal in your stocking.

Daniel John Sobieski is a freelance writer whose pieces have appeared in Investor’s Business Daily, Human Events, Reason Magazine and the Chicago Sun-Times among other publications.

One may be thankful that President Harry S. Truman didn’t have to file an environmental impact statement before he dropped the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, acts which shortened and won World War II and saved hundreds of thousands of lives.

If you wondered why our air campaign against ISIS was inept, consider the statement by Mike Morell, speaking on the “Charlie Rose” program Tuesday night that we didn’t take out the oil facilities that ISIS was using to become the best financed terrorist organization in history because of our concern the environment would be harmed. As the Washington Times reported:

A former CIA director said the U.S.-led coalition fighting the Islamic State has been reluctant to attack oil wells controlled by the extremist group partly because of environmental concerns.

We didn’t go after oil wells -- actually hitting oil wells that ISIS controls because we didn’t want to do environmental damage, and we didn’t want to destroy that infrastructure,” said former spy chief Michael Morell, using an acronym for the Islamic State.

We didn’t go after oil wells -- actually hitting oil wells that ISIS controls because we didn’t want to do environmental damage, and we didn’t want to destroy that infrastructure,” said former spy chief Michael Morell, using an acronym for the Islamic State.

.

President Obama would destroy the American economy to fight the mythical threat of climate change but protected the oil wealth of the very real and very deadly threat of ISIS because destroying it might hurt the environment.

.

[h=1]Free Syrian Army fatwa forbids killing ‘believer lice growing in blessed beards’: report[/h]

The Free Syrian Army has issued a fatwa prohibiting the killing of lice that appear in the Muslim beard or else “be punished with 50 lashes by Sharia,” Ahlulbayt News, an English-language Shia Islamic television channel, reported Sunday.

The fatwa, translated by Ahlulbayt, reportedly states that “blessed lice” appear in the Muslim’s beard because of his “lack of bathing due to the water non-availability all the time on the Jihad [holy war] fronts.” This causes their beards to become moist and thick, which makes it “a natural place for lice to live in.”

“The Sharia Authority in Aleppo recommends the Mujahideen [holy fighters] brothers to dye their beards with Henna, like our prophet Muhammad PBuH, the thing that would reduce the itching caused by the lice, and to maintain this lice that would have not appeared in those blessed beards, if it was not from God’s Muslim believing creatures,” the fatwa reportedly states.

“Who disobeys this Sharia fatwa [advisory opinion] which has been confirmed right by a number of the senior scholars in Aleppo, will be punished with 50 lashes by Sharia, and other measures will be taken against him in the Shaira Court in Aleppo. … And God was behind our intent,” Ahlulbayt reported the fatwa as saying.

According to Ahlulbayt, the fatwa conflicts with Islamic teachings, “as the core teaching of Islam is based on hygiene calling for Muslims to wash 5 times a day before prayers and wash before reading Quran, ablution.”

The Free Syrian Army has issued a fatwa prohibiting the killing of lice that appear in the Muslim beard or else “be punished with 50 lashes by Sharia,” Ahlulbayt News, an English-language Shia Islamic television channel, reported Sunday.

The fatwa, translated by Ahlulbayt, reportedly states that “blessed lice” appear in the Muslim’s beard because of his “lack of bathing due to the water non-availability all the time on the Jihad [holy war] fronts.” This causes their beards to become moist and thick, which makes it “a natural place for lice to live in.”

“The Sharia Authority in Aleppo recommends the Mujahideen [holy fighters] brothers to dye their beards with Henna, like our prophet Muhammad PBuH, the thing that would reduce the itching caused by the lice, and to maintain this lice that would have not appeared in those blessed beards, if it was not from God’s Muslim believing creatures,” the fatwa reportedly states.

“Who disobeys this Sharia fatwa [advisory opinion] which has been confirmed right by a number of the senior scholars in Aleppo, will be punished with 50 lashes by Sharia, and other measures will be taken against him in the Shaira Court in Aleppo. … And God was behind our intent,” Ahlulbayt reported the fatwa as saying.

According to Ahlulbayt, the fatwa conflicts with Islamic teachings, “as the core teaching of Islam is based on hygiene calling for Muslims to wash 5 times a day before prayers and wash before reading Quran, ablution.”

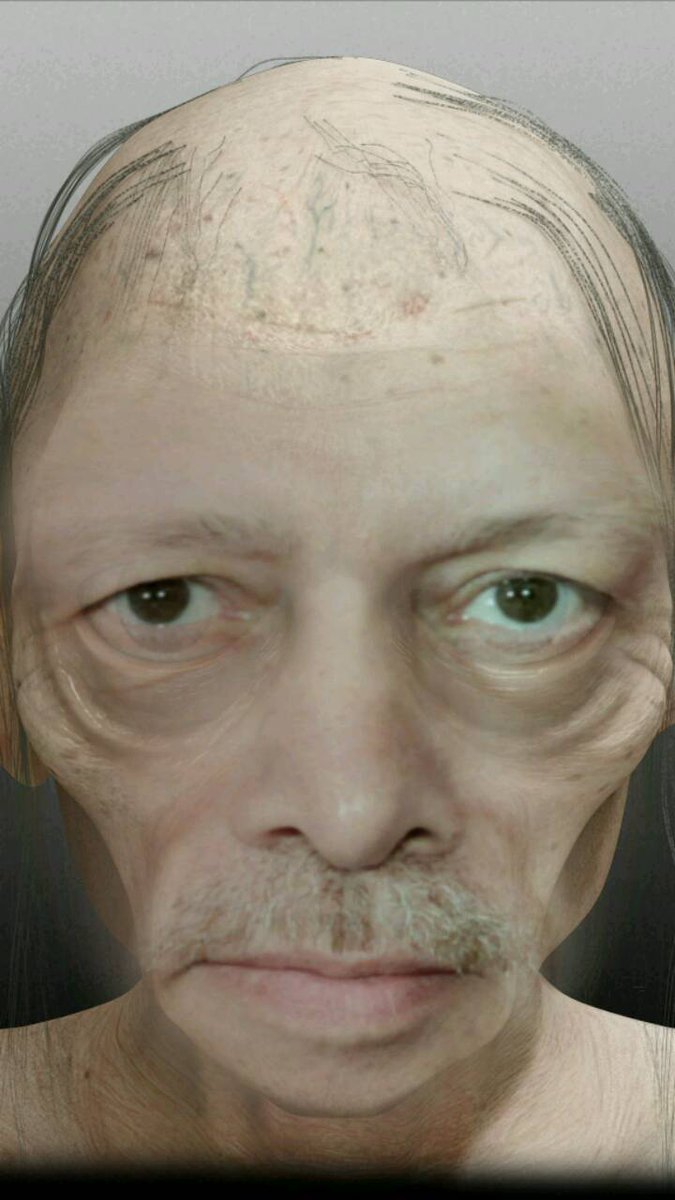

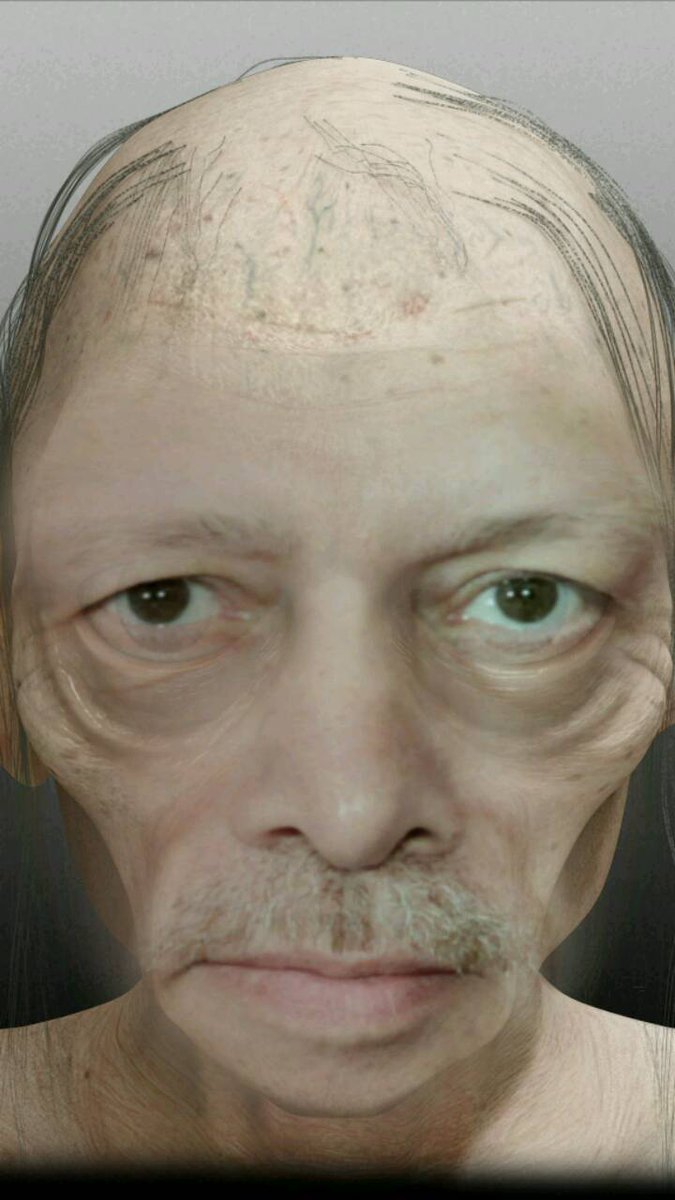

[h=1]Turkish court calls for experts to establish whether Erdogan looks like… Gollum?[/h]

Turkish court has ordered experts to examine whether President Erdogan resembled the “Lord of the Rings” character of Gollum, after memes appeared comparing the two. Depending on their verdict, the author of the joke might face up to 2 years in jail.

The Aydin 3rd Criminal Court of First Instance has called on experts from several fields – two academics, two behavioral scientists or psychologists, and an expert on cinema and television productions – to look into the resemblance between Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and fictional movie character Gollum, the local Sozcu daily reported on Tuesday.

The court is looking into the case to establish whether Dr. Bilgin Ciftci, a physician, insulted the president when he shared a meme comparing Erdogan’s eating habits – as well as emotions such as surprise and amazement – with those of Gollum.

For publishing the meme, Ciftci was expelled from the Public Health Institution of Turkey (THSK) in October.

A medical doctor's job is terminated by the state for sharing this picture#BilginCiftci #AKP @RT_Erdogan

With the court unable to decide whether Erdogan truly looks like the character from the famous fantasy saga, expert help was called only at the fourth hearing.

The prosecutor and the chief judge could make a decision during the previous hearings because they were not familiar with the character, as they had not seen the movies, according to Ciftci’s lawyer Hicran Danisman.

The judge postponed the hearing until February, 13, 2016. If the doctor is found guilty, he may be sentenced up to two years in prison for insulting Erdogan.

Gollum ve RTE'nin yan yana resimlerini paylaşan Dr. Bilgin Çiftçi'nin ihracı istenmiş. Yanındayız... Gollum Tayyip!

Turkish court has ordered experts to examine whether President Erdogan resembled the “Lord of the Rings” character of Gollum, after memes appeared comparing the two. Depending on their verdict, the author of the joke might face up to 2 years in jail.

The Aydin 3rd Criminal Court of First Instance has called on experts from several fields – two academics, two behavioral scientists or psychologists, and an expert on cinema and television productions – to look into the resemblance between Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and fictional movie character Gollum, the local Sozcu daily reported on Tuesday.

The court is looking into the case to establish whether Dr. Bilgin Ciftci, a physician, insulted the president when he shared a meme comparing Erdogan’s eating habits – as well as emotions such as surprise and amazement – with those of Gollum.

For publishing the meme, Ciftci was expelled from the Public Health Institution of Turkey (THSK) in October.

A medical doctor's job is terminated by the state for sharing this picture#BilginCiftci #AKP @RT_Erdogan

With the court unable to decide whether Erdogan truly looks like the character from the famous fantasy saga, expert help was called only at the fourth hearing.

The prosecutor and the chief judge could make a decision during the previous hearings because they were not familiar with the character, as they had not seen the movies, according to Ciftci’s lawyer Hicran Danisman.

The judge postponed the hearing until February, 13, 2016. If the doctor is found guilty, he may be sentenced up to two years in prison for insulting Erdogan.

Gollum ve RTE'nin yan yana resimlerini paylaşan Dr. Bilgin Çiftçi'nin ihracı istenmiş. Yanındayız... Gollum Tayyip!

Doktor Bilgin Çiftçi bu fotodan dolayı memuriyetten men edilmiş. Yalan mı, bal gibi bir Kasımpaşa'lı şizofren Might not even be ISIS Joe. I posted a piece several weeks back about nuclear material from Russan stockpiles being sold to the highest bidder by criminal gangs on the black market.

What's scary as well is, look at the title of this thread. We can't get nation states to agree on a way to fight terror groups without cheating. Turkey cheating on oil. Putin cheating to gain more power and influence, and to keep his boy in power in Syria. Can't even agree where individual planes can fly while the common enemy has no air force!!!

Terrorists emulate the "successful" missions of previous terrorists. Expect gangs of 8-15 in their 20s and 30s to blend into neighborhoods for a few months, renting adjacent apartments etc. Expect this to occur in multiple cities where on a Friday night they do a hostage situation at a movie or concert, a driveby machine gun firing at an outdoor cafe, and a stadium suicide bomb. Others are planning something bigger. It's inevitable.

It has begun. "Self-radicalized." Expect to hear that term a lot in the future.

Russia Adding 2nd Airbase in Syria, Pursuing "Expansion" in Military Campaign - Lucas Tomlinson (FOX News)

Russia has expanded its military operations in Syria to include a second airbase, according to a U.S. official briefed on the latest intelligence from the region.

Moscow's presence has grown to four forward operating bases, including recently added bases in Hama and Tiyas, together with a second airbase in Shayrat, near Homs, in addition to Basel al-Assad airbase in Latakia.

[h=3]The Confrontation between Turkey and Russia: Lessons for Israel[/h] INSS Insight No. 774, December 3, 2015

Amos Yadlin

The confrontation between Turkey and Russia heightens the instability in the Middle East by reducing the possibility of concluding the ongoing crisis in Syria and successfully contending with the Islamic State. Israel can derive a number of tactical and strategic lessons from the confrontation, and in this context, should also underscore that Syria cannot be reunited and the area must be stabilized through a re-demarcation of borders, perhaps within a federative framework.

Yet regardless of the solution found, the lesson from the Turkish-Russian confrontation for all parties involved in Syria is that in the complex Middle East, rivalry between two parties should not be allowed to render a third party acceptable. In other words, the desire to weaken the Islamic State cannot make the Iranian-backed Assad regime any more acceptable, and at the same time, opposition to Russian involvement in Syria cannot make the Islamic State or the al-Nusra Front a legitimate replacement for Assad.

The challenge, then, is to find the right overall strategy, backed by the decisiveness, resources, and ground forces necessary to simultaneously fight Assad and the Salafi jihadist forces in Syria, and in so doing, to create a sustainable reality in this arena.

Israel is not part of the Middle East upheaval and plays almost no active role in it. Whether out of choice or dictated by circumstances, Israeli policy has thus far favored sitting on the fence and observing from the side while developments unfold. Regardless of questions regarding the fundamental wisdom of this policy, current events oblige Israel to internalize and understand the emerging dangers and opportunities in its surroundings. Indeed, in a region that must commonly adapt to new patterns – reflecting frequent changes in the delicate balance among the many actors involved – a new chapter in the complex plot is underway, with the first military confrontation between Turkey and Russia. Turkey’s downing of the Russian plane has both highlighted and sharpened contradictions and truths on the bilateral and international levels.

Above all, this is a clash between two countries whose relations are based on an historic rivalry that is unrelated to the current context. The Russians and the Turks have in the past engaged in full scale military conflicts with one another regarding struggles over control and influence in key regions, particularly the Balkans and the Black Sea, and Ankara regards Moscow as standing threat to its interests. The policies of the current leaders of both countries only fan such tensions. Recep Tayyip Erdogan and Vladimir Putin represent aggressive and ambitious leaders driven by the desire to transform their respective countries into the powers they once were. Indeed, the two heads of state have been referred to as “sultan” and “czar,” implying the figure that each seeks to become.

Second, the already charged relationship between Turkey and Russia has been affected by strategic considerations and political interests relating to the current reality in the Middle East and Europe. The two countries do not see eye to eye regarding the crisis in Syria or the preferable solution. Whereas Turkey has adopted the ultimate goal of Assad’s removal from power, Russia regards Assad’s ongoing rule as a necessary condition for the promotion of stability in the collapsed state and the preservation of its own strategic interests in the Middle East.

Although both countries formally oppose the Islamic State and seek to weaken it, they are actually making use of it to garner legitimacy for their activities in Syria, which are part of efforts of much greater importance to them: Turkey’s efforts against the Kurds and Russia’s efforts against the opposition groups that are not aligned with the Islamic State (the majority of which are supported by Turkey). Against the backdrop of the crisis in Ukraine and the West’s united opposition against Putin (by Turkey’s fellow members in NATO), the conflicting interests of Russia and Turkey in Syria, along with Turkey’s staunch opposition to Russian military intervention in Syria, has placed the two countries on a collision course.

Without a doubt the confrontation between Turkey and Russia heightens the instability in the region by reducing the possibility of concluding the ongoing crisis in Syria and successfully contending with the Islamic State. That being the case, a variety of future scenarios in the Turkish-Russian confrontation are now possible, ranging from containment of the confrontation and a return to normal relations, to mutual diplomatic and economic hostility (as in the case of Turkish-Israeli relations), to military escalation (such as the launching of S-400 missiles or the downing of a Turkish aircraft, a cyber attack, or more extensive military action).

It is difficult to assess which is the most likely scenario, but understanding is growing within Turkey that downing the Russian plane was a far-reaching step. Erdogan has expressed a willingness to issue a veiled apology, and both parties may now begin to conduct themselves with caution. Still, even at this stage, and regardless of the different scenarios, Israel can derive a number of lessons and insights from the confrontation.

The Tactical Lesson

First and foremost, the interception of the Russian plane highlights the minimal room for error; at the same time, the Turks could have exercised restraint and refrained from downing the Russian plane. The radar images released indicate that the Russian aircraft did indeed enter Turkish airspace, but that its penetration was negligible (lasting only 10-15 seconds) and clearly reflected no hostile intent toward Turkey. The plane was not intercepted accidentally, but it is unclear who gave the final authorization for the interception. In Israel, efforts must be made to ensure that such authority remains at the highest possible political and military level.

The unfolding of events, from the moment the decision was made to intercept the plane, highlights the need to ensure maximum control over decision making in the future regarding events with the potential for escalation that might entangle Israel. Although in Israel existing escalation control mechanisms are sufficiently effective, and not all warlike events lead to full scale war, Israel must nonetheless develop strategic thinking regarding mechanisms for preventing escalation and concluding campaigns, even after a proactive or reactive initiated action that is regarded as of essential importance.

On the level of coordination with Russia in light of its military involvement in Syria, Israel must maintain the understandings reached with Russia in October 2015 and consider whether they should now be sharpened, as a lesson based on the incident on the Turkish border. Moreover, the stationing of S-400 missile systems changes the rules of airspace for Israel as well, and requires the establishment of a stringent mechanism to prevent an Israeli-Russian collision. Israel currently has no significant points of friction with Turkey, but must nonetheless derive the right lessons. Turkey has proven that it is not trigger-shy and that it makes good on its threats: approximately two years ago, Turkey warned that it would intercept any plane that violated its sovereignty. Looking ahead, and based on previous clashes (as in the case of the flotilla to Gaza in 2010), it is important that Israel remain mindful of this in the event of a potential confrontation with a Turkish flotilla or aircraft that may approach Israel’s borders in the future.

The Strategic Lesson

The next question, therefore, concerns the Israeli decision whether or not to choose a side in the current conflict between Turkey and Russia, and, if so, which side to pick. With the exception of attacks attributed to it against high quality weapons transferred from Syria to Hezbollah, Israel is not a central actor in the internal conflict in Syria or among the external parties involved, and is certainly not a party to the current confrontation between Turkey and Russia. However, an assessment of Israeli interests regarding this confrontation reveals a complex situation.

On the one hand, on a bilateral level, Israel has a clear interest in supporting Moscow. The two countries enjoy positive, well established, stable relations and have thus far managed to successfully navigate the quagmire of the Russian military presence in Syria. In addition, Israel’s relationship with Turkey under Erdogan is unstable and, since 2009, has been characterized by ongoing hostility that apparently will be difficult to allay as long as Erdogan remains a dominant force in Turkish decision making. Taking Russia’s side may also bring economic benefit to Israel, as Russia has imposed economic sanctions on Turkey, whereas for its part Israel could provide Russia with a partial replacement for Turkey in agriculture, tourism, and other areas.

On the other hand, actually siding with Turkey, which opposes the radical axis in Syria, would better serve Israel’s strategic logic and fundamental interests. Russian operations in Syria, under cover of the struggle against the Islamic State, provide an international seal of approval to Israel’s most dangerous enemies – Iran, Hezbollah, and the Assad regime. In this context, Turkey and Israel share a common interest, which includes Assad’s removal from power, the weakening of Iranian dominance in Syria, and the resulting blow this would mean for Hezbollah. A Turkish signal of willingness to work in cooperation with Israel to address these threats and challenges, and consequently to reduce its hostility toward Israel, would bring to the table other issues with the potential for mutual profits, such as the opening of the Turkish market to Israeli gas (a need that will increase with the reduced supply of Russian gas to Turkey); an improvement in Israeli integration in NATO activity (which has encountered difficulties due to Turkish opposition); and Turkey’s return as a positive and central actor in the political process between Israel and the Palestinians and the Arab world (which is in need of a creative maneuver to break the current impasse).

Perhaps Israel’s contradictory interests in the current confrontation between Turkey and Russia can also shed light on what is the most important goal at the moment, for the United States and the European Union as well: the formulation of a strategy that would lead, whether simultaneously or incrementally, to the weakening and removal of the two negative forces operating in Syria – the Assad regime on the one hand and the Islamic State on the other.

Finding a solution to the crisis in Syria will require joint action incorporating military, diplomatic, and political efforts. Israeli creativity in this context should emphasize the inability to reunite Syria and the need to stabilize the area through a re-demarcation of borders, perhaps within a federative framework. Regardless of the solution found, the lesson from the Turkish-Russian confrontation for all parties involved in Syria is that in the complex Middle East, rivalry between two parties should not be allowed to render a third party acceptable.

In other words, the desire to weaken the Islamic State cannot make the Iranian-backed Assad regime any more acceptable, and at the same time, opposition to Russian involvement in Syria cannot make the Islamic State or the al-Nusra Front a legitimate replacement for Assad. The challenge, then, is to find the right overall strategy, backed by the decisiveness, resources, and ground forces necessary to simultaneously fight Assad and the Salafi jihadist forces in Syria, and in so doing, to create a sustainable reality in this arena.

Amos Yadlin

The confrontation between Turkey and Russia heightens the instability in the Middle East by reducing the possibility of concluding the ongoing crisis in Syria and successfully contending with the Islamic State. Israel can derive a number of tactical and strategic lessons from the confrontation, and in this context, should also underscore that Syria cannot be reunited and the area must be stabilized through a re-demarcation of borders, perhaps within a federative framework.

Yet regardless of the solution found, the lesson from the Turkish-Russian confrontation for all parties involved in Syria is that in the complex Middle East, rivalry between two parties should not be allowed to render a third party acceptable. In other words, the desire to weaken the Islamic State cannot make the Iranian-backed Assad regime any more acceptable, and at the same time, opposition to Russian involvement in Syria cannot make the Islamic State or the al-Nusra Front a legitimate replacement for Assad.

The challenge, then, is to find the right overall strategy, backed by the decisiveness, resources, and ground forces necessary to simultaneously fight Assad and the Salafi jihadist forces in Syria, and in so doing, to create a sustainable reality in this arena.

Israel is not part of the Middle East upheaval and plays almost no active role in it. Whether out of choice or dictated by circumstances, Israeli policy has thus far favored sitting on the fence and observing from the side while developments unfold. Regardless of questions regarding the fundamental wisdom of this policy, current events oblige Israel to internalize and understand the emerging dangers and opportunities in its surroundings. Indeed, in a region that must commonly adapt to new patterns – reflecting frequent changes in the delicate balance among the many actors involved – a new chapter in the complex plot is underway, with the first military confrontation between Turkey and Russia. Turkey’s downing of the Russian plane has both highlighted and sharpened contradictions and truths on the bilateral and international levels.

Above all, this is a clash between two countries whose relations are based on an historic rivalry that is unrelated to the current context. The Russians and the Turks have in the past engaged in full scale military conflicts with one another regarding struggles over control and influence in key regions, particularly the Balkans and the Black Sea, and Ankara regards Moscow as standing threat to its interests. The policies of the current leaders of both countries only fan such tensions. Recep Tayyip Erdogan and Vladimir Putin represent aggressive and ambitious leaders driven by the desire to transform their respective countries into the powers they once were. Indeed, the two heads of state have been referred to as “sultan” and “czar,” implying the figure that each seeks to become.

Second, the already charged relationship between Turkey and Russia has been affected by strategic considerations and political interests relating to the current reality in the Middle East and Europe. The two countries do not see eye to eye regarding the crisis in Syria or the preferable solution. Whereas Turkey has adopted the ultimate goal of Assad’s removal from power, Russia regards Assad’s ongoing rule as a necessary condition for the promotion of stability in the collapsed state and the preservation of its own strategic interests in the Middle East.

Although both countries formally oppose the Islamic State and seek to weaken it, they are actually making use of it to garner legitimacy for their activities in Syria, which are part of efforts of much greater importance to them: Turkey’s efforts against the Kurds and Russia’s efforts against the opposition groups that are not aligned with the Islamic State (the majority of which are supported by Turkey). Against the backdrop of the crisis in Ukraine and the West’s united opposition against Putin (by Turkey’s fellow members in NATO), the conflicting interests of Russia and Turkey in Syria, along with Turkey’s staunch opposition to Russian military intervention in Syria, has placed the two countries on a collision course.

Without a doubt the confrontation between Turkey and Russia heightens the instability in the region by reducing the possibility of concluding the ongoing crisis in Syria and successfully contending with the Islamic State. That being the case, a variety of future scenarios in the Turkish-Russian confrontation are now possible, ranging from containment of the confrontation and a return to normal relations, to mutual diplomatic and economic hostility (as in the case of Turkish-Israeli relations), to military escalation (such as the launching of S-400 missiles or the downing of a Turkish aircraft, a cyber attack, or more extensive military action).

It is difficult to assess which is the most likely scenario, but understanding is growing within Turkey that downing the Russian plane was a far-reaching step. Erdogan has expressed a willingness to issue a veiled apology, and both parties may now begin to conduct themselves with caution. Still, even at this stage, and regardless of the different scenarios, Israel can derive a number of lessons and insights from the confrontation.

The Tactical Lesson

First and foremost, the interception of the Russian plane highlights the minimal room for error; at the same time, the Turks could have exercised restraint and refrained from downing the Russian plane. The radar images released indicate that the Russian aircraft did indeed enter Turkish airspace, but that its penetration was negligible (lasting only 10-15 seconds) and clearly reflected no hostile intent toward Turkey. The plane was not intercepted accidentally, but it is unclear who gave the final authorization for the interception. In Israel, efforts must be made to ensure that such authority remains at the highest possible political and military level.

The unfolding of events, from the moment the decision was made to intercept the plane, highlights the need to ensure maximum control over decision making in the future regarding events with the potential for escalation that might entangle Israel. Although in Israel existing escalation control mechanisms are sufficiently effective, and not all warlike events lead to full scale war, Israel must nonetheless develop strategic thinking regarding mechanisms for preventing escalation and concluding campaigns, even after a proactive or reactive initiated action that is regarded as of essential importance.

On the level of coordination with Russia in light of its military involvement in Syria, Israel must maintain the understandings reached with Russia in October 2015 and consider whether they should now be sharpened, as a lesson based on the incident on the Turkish border. Moreover, the stationing of S-400 missile systems changes the rules of airspace for Israel as well, and requires the establishment of a stringent mechanism to prevent an Israeli-Russian collision. Israel currently has no significant points of friction with Turkey, but must nonetheless derive the right lessons. Turkey has proven that it is not trigger-shy and that it makes good on its threats: approximately two years ago, Turkey warned that it would intercept any plane that violated its sovereignty. Looking ahead, and based on previous clashes (as in the case of the flotilla to Gaza in 2010), it is important that Israel remain mindful of this in the event of a potential confrontation with a Turkish flotilla or aircraft that may approach Israel’s borders in the future.

The Strategic Lesson

The next question, therefore, concerns the Israeli decision whether or not to choose a side in the current conflict between Turkey and Russia, and, if so, which side to pick. With the exception of attacks attributed to it against high quality weapons transferred from Syria to Hezbollah, Israel is not a central actor in the internal conflict in Syria or among the external parties involved, and is certainly not a party to the current confrontation between Turkey and Russia. However, an assessment of Israeli interests regarding this confrontation reveals a complex situation.

On the one hand, on a bilateral level, Israel has a clear interest in supporting Moscow. The two countries enjoy positive, well established, stable relations and have thus far managed to successfully navigate the quagmire of the Russian military presence in Syria. In addition, Israel’s relationship with Turkey under Erdogan is unstable and, since 2009, has been characterized by ongoing hostility that apparently will be difficult to allay as long as Erdogan remains a dominant force in Turkish decision making. Taking Russia’s side may also bring economic benefit to Israel, as Russia has imposed economic sanctions on Turkey, whereas for its part Israel could provide Russia with a partial replacement for Turkey in agriculture, tourism, and other areas.

On the other hand, actually siding with Turkey, which opposes the radical axis in Syria, would better serve Israel’s strategic logic and fundamental interests. Russian operations in Syria, under cover of the struggle against the Islamic State, provide an international seal of approval to Israel’s most dangerous enemies – Iran, Hezbollah, and the Assad regime. In this context, Turkey and Israel share a common interest, which includes Assad’s removal from power, the weakening of Iranian dominance in Syria, and the resulting blow this would mean for Hezbollah. A Turkish signal of willingness to work in cooperation with Israel to address these threats and challenges, and consequently to reduce its hostility toward Israel, would bring to the table other issues with the potential for mutual profits, such as the opening of the Turkish market to Israeli gas (a need that will increase with the reduced supply of Russian gas to Turkey); an improvement in Israeli integration in NATO activity (which has encountered difficulties due to Turkish opposition); and Turkey’s return as a positive and central actor in the political process between Israel and the Palestinians and the Arab world (which is in need of a creative maneuver to break the current impasse).

Perhaps Israel’s contradictory interests in the current confrontation between Turkey and Russia can also shed light on what is the most important goal at the moment, for the United States and the European Union as well: the formulation of a strategy that would lead, whether simultaneously or incrementally, to the weakening and removal of the two negative forces operating in Syria – the Assad regime on the one hand and the Islamic State on the other.

Finding a solution to the crisis in Syria will require joint action incorporating military, diplomatic, and political efforts. Israeli creativity in this context should emphasize the inability to reunite Syria and the need to stabilize the area through a re-demarcation of borders, perhaps within a federative framework. Regardless of the solution found, the lesson from the Turkish-Russian confrontation for all parties involved in Syria is that in the complex Middle East, rivalry between two parties should not be allowed to render a third party acceptable.

In other words, the desire to weaken the Islamic State cannot make the Iranian-backed Assad regime any more acceptable, and at the same time, opposition to Russian involvement in Syria cannot make the Islamic State or the al-Nusra Front a legitimate replacement for Assad. The challenge, then, is to find the right overall strategy, backed by the decisiveness, resources, and ground forces necessary to simultaneously fight Assad and the Salafi jihadist forces in Syria, and in so doing, to create a sustainable reality in this arena.

you know Putin knows he's dealing with a man who's his equal, not a delusional naive lying community organizer that talks to the world like he's talking to his base, while the world laughs at him

Israel's Air Superiority Clouded by New Russian Missiles in Syria - Judah Ari Gross (Times of Israel)

The Israel Air Force's unquestioned supremacy has kept neighboring air forces almost entirely out of Israeli airspace in the country's wars, but with the recent deployment of the Russian S-400 missile defense system in Syria, that absolute primacy is now in question.

The S-400 anti-aircraft system can track and shoot down targets 400 km. away, a range that encompasses half of Israel including Ben-Gurion Airport.

Nonetheless, the people with their finger on the trigger are not enemies, said Yiftah Shapir, a military technology research fellow at the Institute for National Security Studies in Tel Aviv.

In the years following the 1973 war, when Soviet surface-to-air missiles had neutralized IAF attacks, Israel invested heavily in developing weaponry to counteract those anti-aircraft batteries.

For years, Israel has been preparing for the deployment of the S-300 in enemy territory. The S-400 system is simply a more advanced form of the S-300.

"From my understanding of our capabilities, if we wanted to operate in the area protected by the S-400, we could do it. It wouldn't be easy, but possible," said Shapir, who served as a lieutenant colonel in the IAF.

The Israel Air Force's unquestioned supremacy has kept neighboring air forces almost entirely out of Israeli airspace in the country's wars, but with the recent deployment of the Russian S-400 missile defense system in Syria, that absolute primacy is now in question.

The S-400 anti-aircraft system can track and shoot down targets 400 km. away, a range that encompasses half of Israel including Ben-Gurion Airport.

Nonetheless, the people with their finger on the trigger are not enemies, said Yiftah Shapir, a military technology research fellow at the Institute for National Security Studies in Tel Aviv.

In the years following the 1973 war, when Soviet surface-to-air missiles had neutralized IAF attacks, Israel invested heavily in developing weaponry to counteract those anti-aircraft batteries.

For years, Israel has been preparing for the deployment of the S-300 in enemy territory. The S-400 system is simply a more advanced form of the S-300.

"From my understanding of our capabilities, if we wanted to operate in the area protected by the S-400, we could do it. It wouldn't be easy, but possible," said Shapir, who served as a lieutenant colonel in the IAF.

Video: American Paratroopers Train with IDF Special Forces in Israel

A large-scale training exercise was held in Israel this week with 173 American paratroopers and hundreds of fighters from the IDF's elite Egoz guerilla warfare unit.

A large-scale training exercise was held in Israel this week with 173 American paratroopers and hundreds of fighters from the IDF's elite Egoz guerilla warfare unit.

Posting this for everyone's consideration. I agree with some of it but not all of it. We'll see.....

[h=1]December 8, 2015[/h] [h=3]Langfan: Putin has checkmated himself into a lose-lose Syrian debacle[/h] There is no way Putin can come out a winner in the situation he has created for himself.

By Mark Langfan, INN

When Putin first teamed up with Iran and Assad, the two greatest state sponsors of terror in the world, to commit unabashed genocide against the Sunnis of Syria, there was breathless talk that “Putin Checkmated Obama.” It was as if Putin was playing against Obama. Then, after Turkey shot down Putin’s Mig and the Saudis openly declared that they would continue arming their Syrian proxies, the Syrian ground war got even uglier. For all Putin’s bluster, the very ugly reality of Syria has begun to set in.

Putin has never been fighting Obama; he’s been fighting and will have to come to fight hundreds of millions of Sunni Muslims who are coming to see Putin and Russia as the ultimate evil. What’s worse, whether Putin loses, or Putin “wins,” Putin will ultimately lose, lose big, and lose everything.

Let’s look at Putin’s problem objectively. On the one hand, if Putin “loses,” it will be clear he will have militarily lost, and it will be a truly ugly military loss like Afghanistan. If Afghanistan brought down the great and mighty USSR, Syria will bring down little Putin. For, despite Russia’s virtually infinite raids on the Syrian rebels with no limiting rules of engagement, Russian-Iran ground progress has been, at best, severely challenged.

Additionally, with Iran’s soon-in-coming introduction of its own fighter jet squadrons into the Syrian theater to genocidally massacre even more Sunnis, the Saudis and Turks will be forced to deliver shoulder-fired anti-aircraft missiles to take down the Assad barrel-bombs, and the Iranian fighter jets. With those anti-aircraft missiles in Rebels’ hands, Russia will start to suffer catastrophic losses.

Now, on the other hand, in the slim chance Putin “wins,” how exactly does Putin still lose? You have to think backwards from what a Putin end-game “victory” would likely look like. On the current trajectory, if Putin “wins,” he will have to have bulked up his ground forces and airbase footprint so as to be principally occupying Syria. Then what? Whom is Putin going to hand Syria off to after he wins? Are Russian-Orthodox soldiers going to occupy Syria forever? No. The only entity Putin can hand Syria off to is Iran. So, for all Putin’s losses and future costs in terms of Russian lives and money, Russia will not have “won” Syria, Iran will own Syria at Putin’s cost.

You can think of Putin’s egregious behavior as the inverse image of Bush’s actions in tearing the Sunni-centric hierarchical government out of Iraq. Bush destroyed the Sunni power structure in Iraq which ultimately empowered Iran to control Iraq. Putin is saving the Shiite power structure in Syria to ultimately empower Iran to control Syria. Any way you look at it, Putin comes out of Syria with a terrible, perhaps fatal loss to Russia, and a waxing-hegemonic Iran. Putin’s Syrian strategy has also incurred the enmity of 800,000,000 Sunnis so as to strengthen the Shiite Islamists who will then pose an existential threat to Russia. Instead of learning from Bush’s mistake, Putin appears intent on repeating it.

It gets worse. The greatest lie Putin has propagated to himself is that “Assad and Iran are not “Islamist extremist Jihadis.” Hezbollah, and Iran, the underpinnings of Assad’s existence, are not Islamist Jihadis? Hezbollah and Iran are the two greatest Islamist Jihadi-states in the world. The two terrorist States of Hezbollah and Iran have more American and world blood on their hands than anyone else in the world including ISIS. Putin is fighting small-time terrorists, so he can empower big-time terrorists. That’s not “playing chess,” that’s playing Russian Roulette with a fully loaded revolver.

In conclusion, Putin hasn’t checkmated anyone but himself and Russia with his genocidal killing spree of Sunni civilians in Syria. Instead, he has insured another Afghanistan. For, where USSR’s Afghanistan debacle brought about the dismemberment of the Soviet Union, Putin’s Syria debacle will bring the liquidation of Russia.

[h=1]December 8, 2015[/h] [h=3]Langfan: Putin has checkmated himself into a lose-lose Syrian debacle[/h] There is no way Putin can come out a winner in the situation he has created for himself.

By Mark Langfan, INN

When Putin first teamed up with Iran and Assad, the two greatest state sponsors of terror in the world, to commit unabashed genocide against the Sunnis of Syria, there was breathless talk that “Putin Checkmated Obama.” It was as if Putin was playing against Obama. Then, after Turkey shot down Putin’s Mig and the Saudis openly declared that they would continue arming their Syrian proxies, the Syrian ground war got even uglier. For all Putin’s bluster, the very ugly reality of Syria has begun to set in.

Putin has never been fighting Obama; he’s been fighting and will have to come to fight hundreds of millions of Sunni Muslims who are coming to see Putin and Russia as the ultimate evil. What’s worse, whether Putin loses, or Putin “wins,” Putin will ultimately lose, lose big, and lose everything.

Let’s look at Putin’s problem objectively. On the one hand, if Putin “loses,” it will be clear he will have militarily lost, and it will be a truly ugly military loss like Afghanistan. If Afghanistan brought down the great and mighty USSR, Syria will bring down little Putin. For, despite Russia’s virtually infinite raids on the Syrian rebels with no limiting rules of engagement, Russian-Iran ground progress has been, at best, severely challenged.

Additionally, with Iran’s soon-in-coming introduction of its own fighter jet squadrons into the Syrian theater to genocidally massacre even more Sunnis, the Saudis and Turks will be forced to deliver shoulder-fired anti-aircraft missiles to take down the Assad barrel-bombs, and the Iranian fighter jets. With those anti-aircraft missiles in Rebels’ hands, Russia will start to suffer catastrophic losses.

Now, on the other hand, in the slim chance Putin “wins,” how exactly does Putin still lose? You have to think backwards from what a Putin end-game “victory” would likely look like. On the current trajectory, if Putin “wins,” he will have to have bulked up his ground forces and airbase footprint so as to be principally occupying Syria. Then what? Whom is Putin going to hand Syria off to after he wins? Are Russian-Orthodox soldiers going to occupy Syria forever? No. The only entity Putin can hand Syria off to is Iran. So, for all Putin’s losses and future costs in terms of Russian lives and money, Russia will not have “won” Syria, Iran will own Syria at Putin’s cost.

You can think of Putin’s egregious behavior as the inverse image of Bush’s actions in tearing the Sunni-centric hierarchical government out of Iraq. Bush destroyed the Sunni power structure in Iraq which ultimately empowered Iran to control Iraq. Putin is saving the Shiite power structure in Syria to ultimately empower Iran to control Syria. Any way you look at it, Putin comes out of Syria with a terrible, perhaps fatal loss to Russia, and a waxing-hegemonic Iran. Putin’s Syrian strategy has also incurred the enmity of 800,000,000 Sunnis so as to strengthen the Shiite Islamists who will then pose an existential threat to Russia. Instead of learning from Bush’s mistake, Putin appears intent on repeating it.

It gets worse. The greatest lie Putin has propagated to himself is that “Assad and Iran are not “Islamist extremist Jihadis.” Hezbollah, and Iran, the underpinnings of Assad’s existence, are not Islamist Jihadis? Hezbollah and Iran are the two greatest Islamist Jihadi-states in the world. The two terrorist States of Hezbollah and Iran have more American and world blood on their hands than anyone else in the world including ISIS. Putin is fighting small-time terrorists, so he can empower big-time terrorists. That’s not “playing chess,” that’s playing Russian Roulette with a fully loaded revolver.

In conclusion, Putin hasn’t checkmated anyone but himself and Russia with his genocidal killing spree of Sunni civilians in Syria. Instead, he has insured another Afghanistan. For, where USSR’s Afghanistan debacle brought about the dismemberment of the Soviet Union, Putin’s Syria debacle will bring the liquidation of Russia.

hno:

hno:

Liana

Liana