You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Back to the Vegan Talk

- Thread starter Shub

- Start date

-

- Tags

- earnest weirdo chat

#1 killer in this country and worldwide is heart disease which is correlated with diabetes. CAnt clog your arteries with fruits and veggies. #2 is cancer which occurs mostly from dietary factors and environmental factors. You can argue the facts all you want.

Nothing wrong with a diet that contains moderate amount of lean meats, though you want to push your stupid agenda in here, because you are brainwashed.

And there is nothing wrong with enjoying a nice fucking fatty rib-eye on occasion, asshole.

Nothing wrong with a diet that contains moderate amount of lean meats, though you want to push your stupid agenda in here, because you are brainwashed.

And there is nothing wrong with enjoying a nice fucking fatty rib-eye on occasion, asshole.

So fuck the animals huh. Well they say fuck you too

Fuck tom Brady too. He's brainwashed lol

Besides, appealing to Tom Brady on diet issues is a logical fallacy, but you probably don't even know what that is.

<header style="color: rgb(56, 56, 56); font-family: Tahoma, Geneva, sans-serif;">[h=1]Appeal to Authority[/h]</header>argumentum ad verecundiam

(also known as: argument from authority, appeal to false authority, appeal to unqualified authority, argument from false authority, ipse dixit)

Description: Using an authority as evidence in your argument when the authority is not really an authority on the facts relevant to the argument. As the audience, allowing an irrelevant authority to add credibility to the claim being made.

Logical Form:

[COLOR=#C78E0A !important]According to person 1, Y is true.

[COLOR=#C78E0A !important]Therefore, Y is true.[/COLOR]

[/COLOR]

You have a superiority complex, but you probably don't what that is. Listen you little pretentious fuck, you season your meat with plants. Enjoy your recycled protein, jerk.

Actually I don't. I just know a douche bag when I see one. So what if I season my meat with plants, your (lame attempt at a ) point is?

Fact is, you're just not very bright.

if anyone is contemplating on doing a plant based diet, best book out there is the china study.

you have got to be kidding.

Denise Minger showed us that Dr Campbell suffered from severe confirmation bias. I'd love to meet this Denise lady-- i mean she poured loads of time dissecting his work. Of course, with legacy laying in the balance he wrote not 1, but 2 letters challenging her . I'll post her response shortly. She does NOT back down....

https://deniseminger.com/2010/07/07/the-china-study-fact-or-fallac/

<header class="entry-header" style="box-sizing: border-box; width: 620px; margin-bottom: 2.3rem; color: rgb(51, 51, 51); font-family: "Lucida Grande", "Lucida Sans Unicode", "Lucida Sans", Geneva, Verdana, sans-serif;">[h=1]THE CHINA STUDY: FACT OR FALLACY?[/h]</header>[FONT="]Disclaimer: This blog post covers only a fraction of what’s wrong with “The China Study.” In the years since I wrote it, I’ve added a number of additional articles expanding on this critique and covering a great deal of new material. Please read my Forks Over Knives review for more information on what’s wrong with the conclusions drawn from Campbell’s casein/aflatoxin research, and if you’d rather look at peer-reviewed research than the words of some random internet blogger, see my collection of scientific papers based on the China Study data that contradict the claims in Campbell’s book. I’ve also responded to Campbell’s reply to my critique with a much longer, more formal analysis than the one on this page, which you can read here.

When I first started analyzing the original China Study data, I had no intention of writing up an actual critique of Campbell’s much-lauded book. I’m a data junkie. Numbers, along with strawberries and Audrey Hepburn films, make me a very happy girl. I mainly wanted to see for myself how closely Campbell’s claims aligned with the data he drew from—if only to satisfy my own curiosity.

But after spending a solid month and a half reading, graphing, sticky-noting, and passing out at 3 AM from studious exhaustion upon my copy of the raw China Study data, I’ve decided it’s time to voice all my criticisms. And there are many.

First, let me put out some fires before they have a chance to ignite:

- I don’t work for the meat or dairy industry. Nor do I have a fat-walleted roommate, best friend, parent, child, love interest, or highly prodigious cat who works for the meat or dairy industry who paid me off to debunk Campbell.

- Due to food sensitivities, I don’t consume dairy myself, nor do I have any personal reason to promote it as a health food.

- I was a vegetarian/vegan for over a decade and have nothing but respect for those who choose a plant-based diet, even though I am no longer vegan. My goal, with the “The China Study” analysis and elsewhere, is to figure out the truth about nutrition and health without the interference of biases and dogma. I have no agenda to promote.

(IMPORTANT NOTE: My response to Campbell’s reply, as well as to some common reader questions, can be found in the following post: My Response to Campbell. Please read this for clarification regarding univariate correlations and flaws in Campbell’s analytical methods.)

(If this is your first time here, feel free to browse the earlier posts in the China Study category to get up to speed.)

On the Cornell University website (the institution that—along with Oxford University—spawned the China Project), I came across an excellent summary of Campbell’s conclusions from the data. Although this article was published a few years before “The China Study,” it distills some of the book’s points in a concise, down-n’-dirty way. In this post, I’ll be looking at these statements along with other overriding claims in “The China Study” and seeing whether they hold up under scrutiny—including an in-depth look at Campbell’s discoveries with casein.

(Disclaimer: This post is long. Very long. If either your time or your attention span is short, you can scroll down to the bottom, where I summarize the 9,000 words that follow in a less formidable manner.)

(Disclaimer 2: All correlations here are presented as the original value multiplied by 100 in order to avoid dealing with excessive decimals. Asterisked correlations indicate statistical significance, with * = p<0.05, ** = p<0.01, and *** = p<0.001. In other words, the more stars you see, the more confident we are that the trend is legit. If you’re rusty on stats, visit the meat and disease in the China Study page for a basic refresher on some math terms.)

(Disclaimer 3: The China Study files on the University of Oxford website include the results of the China Study II, which was conducted after the first China Study. It includes Taiwan and a number of additional counties on top of the original 65–and thus, more data points. The numbers I use in this critique come solely from the first China Study, as recorded in the book “Diet, Life-style and Mortality in China,” and may be different than the numbers on the website.)

From Cornell University’s article:

“Even small increases in the consumption of animal-based foods was associated with increased disease risk,” Campbell told a symposium at the epidemiology congress, pointing to several statistically significant correlations from the China studies.

Alright, Mr. Campbell—I’ll hear ya out. Let’s take a look at these correlations.

Campbell Claim #1

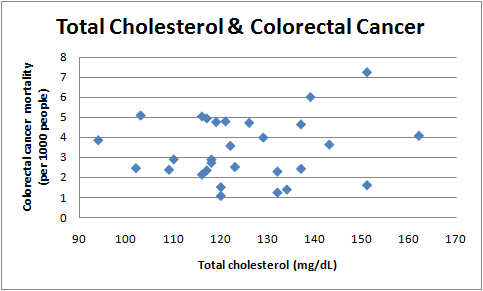

Plasma cholesterol in the 90-170 milligrams per deciliter range is positively associated with most cancer mortality rates. Plasma cholesterol is positively associated with animal protein intake and inversely associated with plant protein intake.

No falsification here. Indeed, cholesterol in the China Project has statistically significant associations with several cancers (though not with heart disease). And indeed, plasma cholesterol correlates positively with animal protein consumption and negatively with plant protein consumption.

But there’s more to the story than that.

Notice Campbell cites a chain of three variables: Cancer associates with cholesterol, cholesterol associates with animal protein, and therefore we infer that animal protein associates with cancer. Or from another angle: Cancer associates with cholesterol, cholesterol negatively associates with plant protein, and therefore we infer plant protein protects against cancer.

But when we actually track down the direct correlation between animal protein and cancer, there is no statistically significant positive trend. None. Looking directly at animal protein intake, we have the following correlations with cancers:

Lymphoma: -18

Penis cancer: -16

Rectal cancer: -12

Bladder cancer: -9

Colorectal cancer: -8

Leukemia: -5

Nasopharyngeal: -4

Cervix cancer: -4

Colon cancer: -3

Liver cancer: -3

Oesophageal cancer: +2

Brain cancer: +5

Breast cancer: +12

Most are negative, but none even reach statistical significance. In other words, the only way Campbell could indict animal protein is by throwing a third variable—cholesterol—into the mix. If animal protein were the real cause of these diseases, Campbell should be able to cite a direct correlation between cancer and animal protein consumption, which would show that people eating more animal protein did in fact get more cancer.

But what about plant protein? Since plant protein correlates negatively with plasma cholesterol, does that mean plant protein correlates with lower cancer risk? Let’s take a look at the cancer correlations with “plant protein intake”:

Nasopharyngeal cancer: -40**

Brain cancer: -15

Liver cancer: -14

Penis cancer: -4

Lymphoma: -4

Bladder cancer: -3

Breast cancer: +1

Stomach cancer: +10

Rectal cancer: +12

Cervix cancer: +12

Colon cancer: +13

Leukemia: +15

Oesophageal cancer +18

Colorectal cancer: +19

We have one statistically significant correlation with a rare cancer not linked to diet (nasopharyngeal cancer), but we also have more positive correlations than we saw with animal protein.

In fact, when we look solely at the variable “death from all cancers,” the association with plant protein is +12. With animal protein, it’s only +3. So why is Campbell linking animal protein to cancer, yet implying plant protein is protective against it?

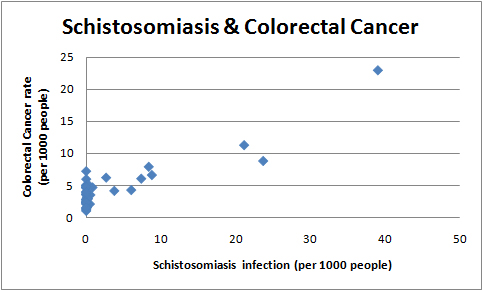

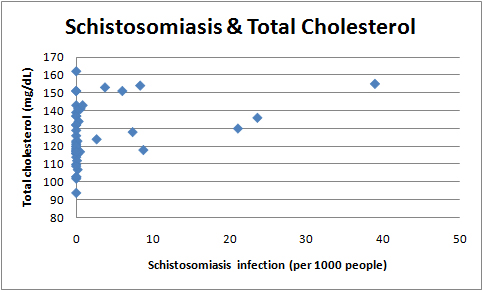

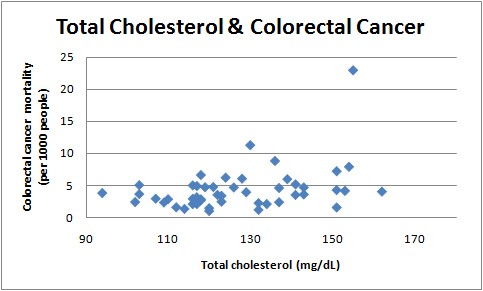

In addition, Campbell’s statement about cholesterol and cancer leaves out a few significant points. What he doesn’t mention is that plasma cholesterol is also associated with several non-nutritional variables known to raise cancer risk—namely schistosomiasis infection (correlation of +34*) and hepatitis B infection (correlation of +30*).

Not coincidentally, cholesterol’s strongest cancer links are with liver cancer, rectal cancer, colon cancer, and the sum of all colorectal cancers. As we saw in the posts on meat consumption and fish consumption, schistosomiasis and hepatitis B are the two biggest factors in the occurrence of these diseases. So is it higher cholesterol (by way of animal products) that causes these cancers, or is it a misleading association because areas with high cholesterol are riddled with other cancer risk factors? We can’t know for sure, but it does seem odd that Campbell never points out the latter scenario as a possibility.

Campbell Claim #2

Breast cancer is associated with dietary fat (which is associated with animal protein intake) and inversely with age at menarche (women who reach puberty at younger ages have a greater risk of breast cancer).

Campbell is correct that breast cancer negatively relates to the age of first menstruation—a correlation of -20. Not statistically significant, but given what we know about hormone exposure and breast cancer, it certainly makes sense. And there is a correlation between fat intake and breast cancer—a non-statistically-significant +18 for fat as a percentage of total calories and +22 for total lipid intake. But are there any dietary or lifestyle factors with a similar or stronger association than this? Let’s look at the correlation between breast cancer and a few other variables. Asterisked items are statistically significant:

Blood glucose level: +36**

Wine intake: +33*

Alcohol intake: +31*

Yearly fruit consumption: +25

Percentage of population working in industry: +24

Hexachlorocyclohexane in food: +24

Processed starch and sugar intake: +20

Corn intake: +20

Daily beer intake: +19

Legume intake: +17

Looks to me like breast cancer may have links with sugar and alcohol, and perhaps also with hexachlorocyclohexane and occupational hazards associated with industry work. Again, why is Campbell singling out fat from animal products when other—stronger—correlations are present?

Certainly, consuming dairy and meat from hormone-injected livestock may logically raise breast cancer risk due to increased exposure to hormones, but this isn’t grounds for generalizing all animal products as causative for this disease. Nor is a correlation of +18 for fat calories grounds for indicting fat as a breast cancer risk factor, when alcohol, processed sugar, and starch correlate even more strongly. (Animal protein itself, for the record, correlates with breast cancer at +12—which is lower than breast cancer’s correlation with light-colored vegetables, legume intake, fruit, and a number of other purportedly healthy plant foods.)

Campbell Claim #3

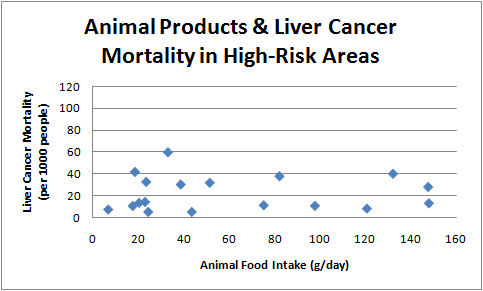

For those at risk for liver cancer (for example, because of chronic infection with hepatitis B virus) increasing intakes of animal-based foods and/or increasing concentrations of plasma cholesterol are associated with a higher disease risk.

Ah, here’s one that may be interesting! Even if animal products don’t cause cancer, do they spur its occurrence when other risk factors are present? That would certainly be in line with Campbell’s research on aflatoxin and rats, where the milk protein casein dramatically increased cancer rates.

So, let’s look only at the counties with the highest rates of hepatitis B infection and see what animal food consumption does there. In the China Study, one documented variable is the percentage of each county’s population testing positive for the hepatitis B surface antigen. Population averages ranged from 1% to 29%, with a mean of 13% and median of 14%. If we take only the counties that have, say, 18% or more testing positive, that leaves us with a solid pool of high-risk data points to look at.

Animal product consumption in these places ranges from a meager 6.9 grams per day to a heftier 148.1 grams per day—a wide enough range to give us a good variety of data points. Liver cancer mortality ranges from 5.51 to 59.63 people per thousand.

Let’s crunch these numbers, shall we? Here’s a chart of the data I’m using.

When we map out liver cancer mortality and animal product consumption only in areas with high rates of hepatitis B infection (18% and higher), we should see cancer rates rise as animal product consumption increases—at least, according to Campbell. That would indicate animal-based foods do encourage cancer growth. But here’s what we really get.

In these high-risk areas for liver cancer, total animal food intake has a correlation with liver cancer of… dun dun dun… +1.

That’s it. One. We rarely get a perfect statistical zero in the real world, but this is pretty doggone close to neutral. Broken up into different types of animal food rather than total consumption, we have the following correlations:

- Meat correlates at -7 with liver cancer in high-risk counties

- Fish correlates at +11

- Eggs correlate at -29

- Dairy correlates at -19

Campbell mentioned plasma cholesterol also associates with liver cancer, which is correct: The raw correlation is a statistically significant +37. If it’s true blood cholesterol is somehow an instigator for liver cancer in hepatitis-B-riddled populations, we’d expect to see this correlation preserved or heightened among our highest-risk counties. So let’s take a look at the same previous 19 counties with high hepatitis B occurrence, and graph their total cholesterol alongside their liver cancer rates.

In the high-risk groups, the correlation between total cholesterol and liver cancer drops from +37 to +8. Still slightly positive, but not exactly damning.

If I were Campbell, I’d look at not only animal protein and cholesterol in relation to liver cancer, but also at the many other variables that correlate positively with the disease. For instance, daily liquor intake correlates at +33*, total alcohol intake correlates at +28*, cigarette use correlates at +27*, intake of the heavy metal cadmium correlates at +38**, rapeseed oil intake correlates at +25*—so on and so forth. All are statistically significant. Why doesn’t Campbell mention these factors as possible causes of increased liver cancer in high-risk areas? And, more importantly, why doesn’t Campbell account for the fact that many of these variables occur alongside increased cholesterol and animal product consumption, making it unclear what’s causing what?

Campbell Claim #4

Cardiovascular diseases are associated with lower intakes of green vegetables and higher concentrations of apo-B (a form of so-called bad blood cholesterol) which is associated with increasing intakes of animal protein and decreasing intakes of plant protein.

Alright, we’ve got a multi-parter here. First, let’s see what the actual correlations are between cardiovascular diseases and green vegetables—an interesting connection, if it holds true. The China Study accounted for this variable in two ways: one through a diet survey that measured how many grams of green vegetables each county averaged per day, and one through a questionnaire that recorded how many times per year citizens ate green vegetables.

From the diet survey, green vegetable intake (average grams per day) has the following correlations:

Myocardial infarction and coronary heart disease: +5

Hypertensive heart disease: -4

Stroke: -8

From the questionnaire, green vegetable intake (times eaten per year) has the following correlations:

Myocardial infarction and coronary heart disease: -43**

Hypertensive heart disease: -36*

Stroke: -35*

A little odd, oui? When we look at total quantity of green vegetables consumed (in terms of weight), we’ve got only weak negative associations for two cardiovascular conditions, and a slightly positive association for heart attacks (myocardial infarction) and coronary heart disease. Nothing to write home about. But when we look at the number of times per year green vegetables are consumed, we have much stronger inverse associations with all cardiovascular diseases. Why the huge difference? Why would frequency be more protective than quantity? What accounts for this mystery?

It could be that the China Study diet survey did a poor job of tracking and estimating greens intake on a long-term basis (indeed, it was only a three-day survey, although when repeated at a later date yielded similar results for each county). But the explanation could also boil down to one word: geography.

Let me explain.

The counties in China that eat greens year-round live in a particular climate and latitude—namely, humid regions to the south. The “Green vegetable intake, times per year” variable has a correlation of -68*** with aridity (indicating a humid climate) and a correlation of -60*** with latitude (indicating southerly placement on the ol’ map). Folks living in these regions might not eat the most green vegetables quantity-wise, but they do eat them frequently, since their growing season is nearly year-round.

In contrast, the variable “Green vegetable intake, grams per day” has a correlation of only -16 with aridity and +5 with latitude, indicating much looser associations with southern geography. The folks who eat lots of green veggies don’t necessarily live in climates with a year-round growing season, but when green vegetables are available, they eat a lot of them. That bumps up the average intake per day, even if they endure some periods where greens aren’t on the menu at all.

If green vegetables themselves were protective of heart disease, as Campbell seems to be implying, we would expect their anti-heart-disease effects to be present in both quantity of consumption and frequency of consumption. Yet the counties eating the most greens quantity-wise didn’t have any less cardiovascular disease than average. This tells us there’s probably another variable unique to the southern, humid regions in China that confers heart disease protection—but green veggies aren’t it.

Some of the hallmark variables of humid southern regions include high fish intake, low use of salt, high rice consumption (and low consumption of all other grains, especially wheat), higher meat consumption, and smaller body size (shorter height and lower weight). And as you’ll see in an upcoming post on heart disease, these southerly regions also had more intense sunlight exposure and thus more vitamin D—an important player in heart disease prevention.

(And for the record, as a green-veggie lover myself, I’m not trying to negate their health benefits—promise! I just want to offer equal skepticism to all claims, even the ones I’d prefer to be true.)

Basically, Campbell’s implication that green vegetables are associated with less cardiovascular disease is misleading. More accurately, certain geographical regions have strong correlations with cardiovascular disease (or lack thereof), and year-round green vegetable consumption is simply an indicator of geography. Since only frequency and not actual quantity of greens seems protective of heart disease and stroke, it’s safe to say that greens probably aren’t the true protective factor.

So that about covers it for greens. What about the next variable in Campbell’s claim: a “bad” form of cholesterol called apo-B?

Campbell is justified in noting the link between apolipoprotein B (apo-B) and cardiovascular disease in the China Study data, a connection widely recognized by the medical community today. These are its correlations with cardiovascular disease:

Myocardial infarction and coronary heart disease: +37**

Hypertensive heart disease: +35*

Stroke: +35*

And he’s also right about the negative association between apo-B and plant protein, which is -37*, as well as the positive association between apo-B and animal protein, which is +25* for non-fish protein and +16 for fish protein. So from a technical standpoint, Campbell’s statement (aside from the green veggie issue) is legit.

However, it’s the implications of this claim that are misleading. From what Campbell asserts, it would seem that animal products are ultimately linked to cardiovascular diseases and plant protein is ultimately protective of those diseases, and apo-B is merely a secondary indicator of this reality. But does that claim hold water? Here’s the raw data.

Correlations between animal protein and cardiovascular disease:

Myocardial infarction and coronary heart disease: +1

Hypertensive heart disease: +25

Stroke: +5

Correlations between fish protein and cardiovascular disease:

Myocardial infarction and coronary heart disease: -11

Hypertensive heart disease: -9

Stroke: -11

Correlations between plant protein and cardiovascular disease (from the China Study’s “diet survey”):

Myocardial infarction and coronary heart disease: +25

Hypertensive heart disease: -10

Stroke: -3

Correlations between plant protein and cardiovascular disease (from the China Study’s “food composite analysis”):

Myocardial infarction and coronary heart disease: +21

Hypertensive heart disease: 0

Stroke: +12

Check that out! Fish protein looks weakly protective all-around; non-fish animal protein is neutral for coronary heart disease/heart attacks and stroke but associates positively with hypertensive heart disease (related to high blood pressure); and plant protein actually correlates fairly strongly with heart attacks and coronary heart disease. (The China Study documented two variables related to plant protein: one from a lab analysis of foods eaten in each county, and one from a diet survey given to county citizens.) Surely, there is no wide division here between the protective or disease-causing effects of animal-based protein versus plant protein. If anything, fish protein looks the most protective of the bunch. No wonder Campbell had to cite a third variable in order to vilify animal products and praise plant protein: Examined directly, they’re nearly neck-and-neck.

If you’re wondering about the connection between animal protein and hypertensive heart disease, by the way, it’s actually hiked up solely by the dairy variable. Here are the individual correlations between specific animal foods and hypertensive heart disease:

Milk and dairy products intake: +30**

Egg intake: -28

Meat intake: -4

Fish intake: -14

You can read more about the connection between dairy and hypertensive heart disease in the entry on dairy in the China Study.

At any rate, Campbell accurately points out that apo-B correlates positively with cardiovascular diseases. But to imply animal protein is causative of these diseases—and green vegetables or plant protein protective of them—is dubious at best. What factors cause both apo-B and cardiovascular disease risk to increase hand-in-hand? This is the question we should be asking.

Campbell Claim #5

Colorectal cancers are consistently inversely associated with intakes of 14 different dietary fiber fractions (although only one is statistically significant). Stomach cancer is inversely associated with green vegetable intake and plasma concentrations of beta-carotene and vitamin C obtained only from plant-based foods.

This is congruous with conventional beliefs about fiber being helpful for colon health. And as a plant-nosher myself, I hope it’s true—but that’s no reason to omit this claim from critical examination. Here are all of the China Study’s fiber variables as they correlate to colorectal cancer:

Total fiber intake: -3

Total neutral detergent fiber intake: -13

Hemi-cellulose fiber intake: -10

Cellulose fiber intake: -13

Intake of lignins remaining after cutin removed: -9

Cutin intake: -14

Starch intake: -1

Pectin intake: +3

Rhamnose intake: -26*

Fucose intake: +2

Arabinose intake: -18

Xylose intake: -15

Mannose intake: -13

Galactose intake: -24

Surprise, surprise: I agree with Campbell on this one! All but two of the fiber variables have inverse associations with colorectal cancers. The first part of Campbell Claim #5 passes Denise’s BS-o-Meter test. Let us celebrate!

…But before we get too jiggy with it, I do have a nit to pick. Fiber intake also negatively correlates with schistosomiasis infection, a type of parasite. Try Googling “schistosomiasis and colorectal cancer” and you’ll get more relevant hits than you’ll ever have time to read. I’ll elaborate on this in a few paragraphs, so hang tight—but for now, I’ll just point out two things:

- Schistosomiasis infection is a very strong predictor for colon and rectal cancers, more so than any of the other hundreds of variables studied in the China Project (it has a correlation of +89 with colorectal cancer).

- The only fiber factions that don’t appear protective of colorectal cancer (pectin and fucose) also have the most neutral associations with schistosomiasis infection (+1 and -5, respectively—whereas other fiber factions had correlations ranging from -9 to -27 with schistosomiasis). In all cases, the correlation between each fiber faction and colorectal cancer parallels its correlation with schistosomiasis.

There is research conducted outside of the China Project suggesting fiber benefits colon health, but often that association dissolves when researchers adjust for other dietary risk factors, such as with the this pooled analysis of colorectal cancer studies published in the Journal of the American Medical Association. Bottom line: It’s never a good idea to go looking for a specific trend just because we believe it should be there. Chains of confirmation bias are often what cause nutritional myths to emerge and persist. Fiber may be beneficial, but we shouldn’t approach the data already expecting to find this—lest we overlook other important influences.

Moving on. Now, what about the second part of this claim: Stomach cancer is inversely associated with green vegetable intake and plasma concentrations of beta-carotene and vitamin C obtained only from plant-based foods.

Is this a fair assessment? Let’s find out. Here are the correlations between stomach cancer and each of these variables.

Green vegetables, daily intake: +5

Green vegetables, times eaten per year: -35**

Plasma beta-carotene: -14

Plasma vitamin C: -13

Ah, looks like we’re facing the Green Veggie Paradox once again. The folks with year-round access to green vegetables get less stomach cancer, but the the folks who eat more green vegetables overall aren’t protected. Once again, I’ll suggest that a geographic variable specific to veggie-growing regions could be at play here.

As for beta-carotene and vitamin C concentrations in the blood, Campbell is correct in noting an inverse association with stomach cancer. However, the correlations aren’t statistically significant, nor are they very high: -14 and -13, respectively.

Campbell Claim #6

Western-type diseases, in the aggregate, are highly significantly correlated with increasing concentrations of plasma cholesterol, which are associated in turn with increasing intakes of animal-based foods.

From his book, we know Campbell defines Western-type diseases as including heart disease, diabetes, colorectal cancers, breast cancer, stomach cancer, leukemia, and liver cancer. And indeed, the variable “total cholesterol” correlates positively with many of these diseases:

Myocardial infarction and coronary heart disease: +4

Diabetes: +8

Colon cancer: +44**

Rectal cancer: +30*

Colorectal cancer: +33**

Breast cancer: +19

Stomach cancer: +17

Leukemia: +26*

Liver cancer: +37*

Perhaps surprisingly, total cholesterol has only weak associations with heart disease and diabetes—weaker, in fact, than the correlation between these conditions and plant protein intake (+25 and +12, respectively). But we’ll put that last point aside for the time being. For now, let’s focus on the diseases with statistical significance, which include all forms of colorectal cancer, leukemia, and liver cancer. (Despite classifying stomach cancer as a “Western disease,” by the way, China actually has far higher rates of this disease than any Western nation. In fact, half the people who die each year from stomach cancer live in China.)

First, let’s dive into the dark, murky chambers of the digestive tract and start with colorectal cancers. Off we go!

What Campbell overlooks about colorectal cancers and cholesterol

As I mentioned earlier, a little somethin’ called “schistosomiasis” is a profoundly strong risk factor for developing colon cancer and rectal cancer. In the China Study data, schistosomiasis correlates at +89*** with colorectal cancer mortality. Yes, 89—higher than any of the other 367 variables recorded.

This, ladies and gentlemen, is what we call a positive correlation.

It just so happens that total cholesterol also correlates with schistosomiasis infection, at a statistically significant rate of +34*:

Basically, this means that areas with higher cholesterol levels also had—for whatever reason—a higher incidence of schistosomiasis infection. It’s hard to say for sure why this is, but it’s likely that the high-cholesterol and high-schistosomiasis groups had a third variable in common, such as infected drinking water or other source of schistosomiasis exposure.

From this alone, it shouldn’t be too shocking that higher cholesterol also correlates with higher rates of colorectal cancer (+33*):

Clearly, we have three tangled-up variables to sort through: total cholesterol, colorectal cancer rates, and schistosomiasis infection. Is it really higher cholesterol that increases the risk of developing colon and rectal cancers, or is the influence of schistosomiasis deceiving us?

To figure this out, let’s look at what cholesterol and colorectal cancer rates look like only in regions with zero schistosomiasis infection. If cholesterol is a causative factor for colorectal cancers, then cancer rates should still increase as total cholesterol rises.

The above graph showcases a correlation of +13. Still positive, but not statistically significant, and a major downgrade from the original correlation of +33*. It does seem schistosomiasis inflates the correlation between cholesterol and colorectal cancers—something Campbell never takes into account. Is blood cholesterol still a risk factor? It’s possible, but we would need more data to know whether the +13 correlation persists or whether there are additional confounding variables at work. For instance, beer intake is another factor correlating significantly with both total cholesterol (+32*) and colon cancer (+40**). If we remove the three counties that drink the most beer from of the data set above, the correlation between cholesterol and and colorectal cancer drops to -9.

See how tricky the interplay of variables can be?

What Campbell overlooks about leukemia and cholesterol

Next in our lineup of “Western diseases” is leukemia, which has a statistically significant correlation of +26* with total cholesterol. (Although the implication here is that animal product consumption raises leukemia risk, it should be noted that animal protein intake itself has a correlation of -5 with leukemia, whereas plant protein actually has a correlation of +15 with this disease. But let’s humor this claim anyway by looking solely at the role of blood cholesterol.)

If you’ll recall from the post on fish and disease in the China Study, leukemia correlates very strongly with working in industry (+53**) and inversely with working in agriculture (-53**). Although it’s possible the cause is nutritional, it’s also quite likely that an occupational hazard is to blame—such as benzene exposure, which is a major and well-known cause of leukemia in Chinese factory and refinery workers.

Lo and behold, cholesterol also correlates strongly with working in industry (+45**) and inversely with working in agriculture (-46**). If an industry-related risk factor raises leukemia rates, it could very well appear as a false correlation with cholesterol. How can we tell if this is the case?

Let’s try looking at the correlation between leukemia and cholesterol only in counties where few members of the population were employed in industry. If cholesterol itself heightens leukemia risk, our positive trend should still be in place. In the China Study data set, the range for percent of the population working in industry is 1.1% to 41.3%, so let’s try looking at the counties where the value is under 10%:

For the low-industry counties, the correlation between leukemia and total cholesterol is close to neutral—a mere +4. As you can see, this is hardly a damning trend. And in case you’re wondering if higher cholesterol could possibly spur the rates of leukemia in folks who are already at risk, this isn’t the case either: Using only counties that had 20% or more of the population working in industry, presumably the folks who had the most exposure to chemicals like benzene, the correlation between cholesterol and leukemia is a slightly protective -3.

What Campbell overlooks about liver cancer and cholesterol

I may not be vegan, but that doesn’t mean I like beating dead horses. Instead of rehashing the earlier analysis of liver cancer under Campbell Claim #3, I’ll just repeat that cholesterol does nothave a significant correlation with liver cancer when you divide the data set into separate groups: areas with high hepatitis B rates an areas with low hepatitis B rates.

From page 104 of his book:

Liver cancer rates are very high in rural China, exceptionally high in some areas. Why was this? The primary culprit seemed to be chronic infection with hepatitis B virus (HBV). …

… But there’s more. In addition to the [hepatitis B] virus being a cause of liver cancer in China, it seems that diet also plays a key role. How do we know? The blood cholesterol levels provided the main clue. Liver cancer is strongly associated with increasing blood cholesterol, and we already know that animal-based foods are responsible for increases in cholesterol.

Campbell connects some of the dots, but misses a very important one. Indeed, hepatitis B associates strongly with liver cancer. Indeed, cholesterol associates with liver cancer. But what he doesn’t mention is that cholesterol also associates with hepatitis B infection. In other words, the groups with higher cholesterol are already at greater risk of liver cancer than groups with lower cholesterol—but it’s not because of diet.

In addition to greater rates of hepatitis B infection, higher-cholesterol areas had additional risk factors for liver cancer, such beer consumption, which also inflated the trend. Despite Campbell’s claims, cholesterol itself does not appear to significantly heighten cancer rates in at-risk populations.

Given Campbell’s casein research and earlier observations about the animal-protein consuming children in the Philippines getting more liver cancer, I wonder if Campbell approached the China Study already expecting a particular outcome. In a massive data set with 8,000 statistically significant correlations, even a smidgen of confirmation bias can cause someone to find a trend that isn’t truly there.

An example of bias in “The China Study”

Body weight, associated with animal protein intake, was associated with more cancer and more coronary heart disease. It seems that being bigger, and presumably better, comes with very high costs. (Page 102)

Consuming more protein was associated with greater body size. … However, this effect was primarily attributed to plant protein, because it makes up 90% of the total Chinese protein intake. (Page 103)

Let’s read between the lines. Here we have Campbell claiming two things, a few paragraphs apart: One, that body weight is associated with more cancer and heart disease, and two, that body size in China is linked not only with a greater intake of animal protein, but also with a greater intake of plant protein. In fact, the link between body size is stronger with plant protein than with animal protein.

Yet notice how Campbell only implicates animal protein in the association between body weight, cancer, and heart disease. If he were to describe the data without bias, Campbell’s first statement would be this:

Body weight, associated with animal protein intake and plant protein intake, was associated with more cancer and more coronary heart disease.

Maybe his editor just overlooked that omission, eh? Right afterward, Campbell notes:

But the good news is this: Greater plant protein intake was closely linked to greater height and body weight. Body growth is linked to protein in general and both animal and plant proteins are effective! (Page 102)

Wait a minute. This is good news? Didn’t Campbell just say being bigger “comes with very high costs” and that it’s associated with “more cancer and coronary heart disease?” Why is body size a bad thing when it’s associated with animal protein, but a good thing when it’s associated with plant protein?

Does less animal foods equal better health?

People who ate the most animal-based foods got the most chronic disease. Even relatively small intakes of animal-based food were associated with adverse effects. People who ate the most plant-based foods were the healthiest and tended to avoid chronic disease.

This oft-repeated quote from “The China Study” is compelling, but is it true? Based on the data above, it seems like an unlikely conclusion—but let’s try once more to see if it could be valid.

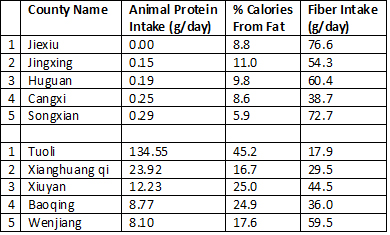

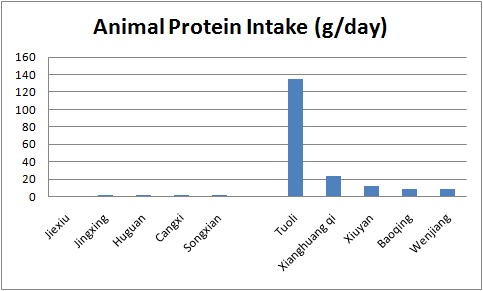

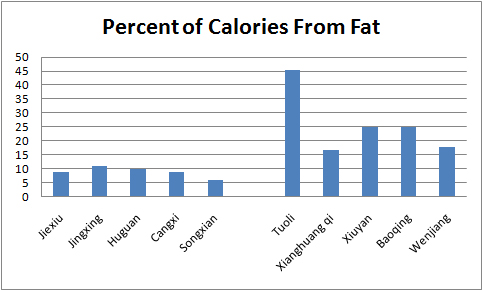

As an illustrative experiment, let’s look at the top five Chinese counties with the lowest animal protein consumption and compare them against the top five counties with the highest animal protein consumption. A data set of 10 won’t yield any confident conclusions, of course, and I won’t treat this as representative of the collective body of China Study data. But since animal protein consumption among the studied counties ranged from 0 grams* to almost 135 grams per day, we should see a stark contrast between the nearly-vegan regions and the ones eating considerably more animal foods. That is, assuming it’s true that “even relatively small intakes of animal-based food” yield disease.

*The county averaging zero grams per day wasn’t completely vegan, but the yearly consumption of animal foods was low enough so that the daily average appeared less than 0.01 grams.

Here are the counties I’ll be using. The first five are our near-vegans; the second five are our highest animal product consumers. From both groups, I had to exclude a top-five county due to missing data for most mortality variables (illegible documentation, according to the authors of “Diet, Life-style and Mortality in China”) and replaced it with a sixth county where animal protein consumption matched within a few hundredths of a gram.

Below are the names of each county, as well as values for their daily animal protein intake, the percentage of their total caloric intake coming from fat, and their daily intake of fiber (in case the latter two variables are also of interest).

To give you a visual idea of these quantities, 135 grams of animal protein is the equivalent of 22 medium eggs per day, 24 grams of animal protein is the equivalent of four medium eggs per day, 12 grams is two eggs, and 9 grams is one and a half eggs. Obviously, that’s quite a wide range even among the top consumers of animal foods, so the highest animal-food-eating counties (Tuoli and XIanghuang qi) may be the most important to study in contrast with the near-vegan counties.

Animal protein intake by county:

For reference, some other diet variables:

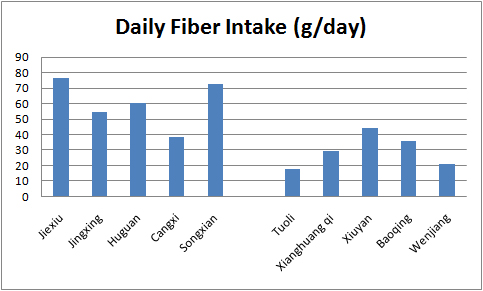

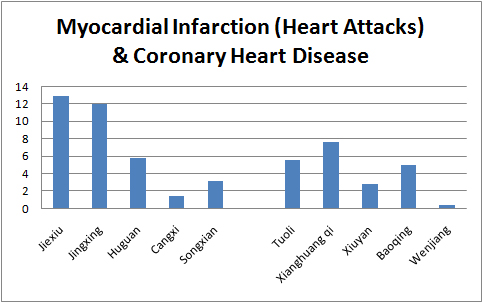

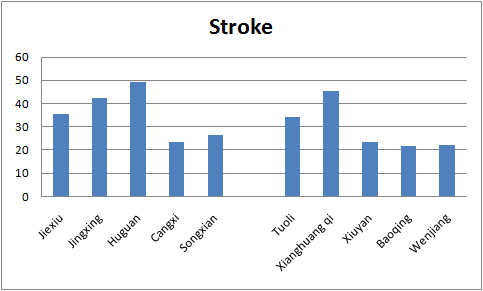

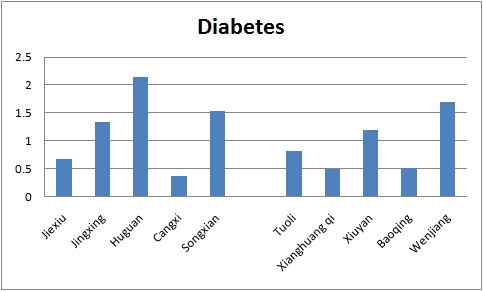

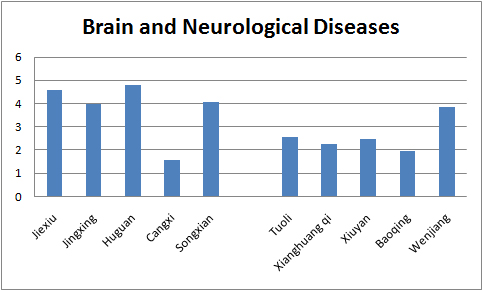

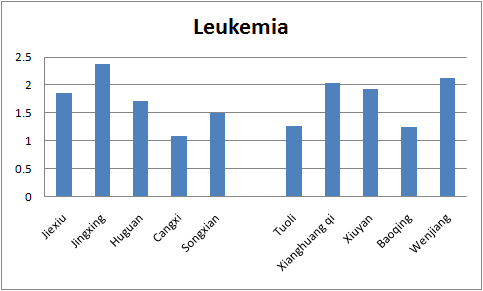

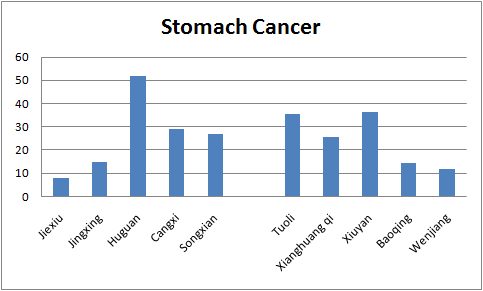

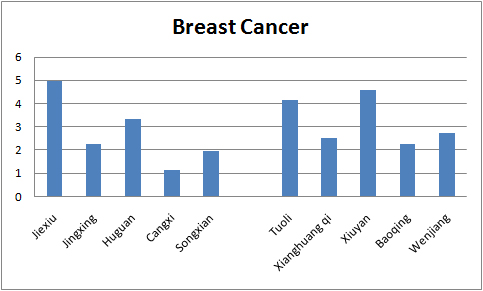

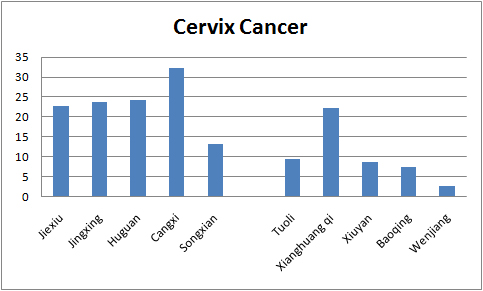

And now, mortality rates for important variables (as per 1000 people). I’ll save you my commentary and just show you the graphs, which should speak for themselves. Remember, the five left-most bars (Jiexiu through Songxian) on each graph are the near-vegan counties, and the five right-most bars (Tuoli through Wenjiang) are the highest consumers of animal products.

As you can see, the mortality rates for both groups (near-vegan and higher-animal-foods) are quite similar, with the animal food group coming out more favorably in some cases (death from all cancers, myocardial infarction, brain and neurological diseases, lymphoma, cervix cancer). This little comparison might not carry a lot of scientific clout due to its small sample size, but it does blatantly undermine Campbell’s assessment:

People who ate the most animal-based foods got the most chronic disease … People who ate the most plant-based foods were the healthiest and tended to avoid chronic disease.

Sins of omission

Perhaps more troubling than the distorted facts in “The China Study” are the details Campbell leaves out.

Why does Campbell indict animal foods in cardiovascular disease (correlation of +1 for animal protein and -11 for fish protein), yet fail to mention that wheat flour has a correlation of +67 with heart attacks and coronary heart disease, and plant protein correlates at +25 with these conditions?

Speaking of wheat, why doesn’t Campbell also note the astronomical correlations wheat flour has with various diseases: +46 with cervix cancer, +54 with hypertensive heart disease, +47 with stroke, +41 with diseases of the blood and blood-forming organs, and the aforementioned +67 with myocardial infarction and coronary heart disease? (None of these correlations appear to be tangled with any risk-heightening variables, either.)

Why does Campbell overlook the unique Tuoli peoples documented in the China Study, who eat twice as much animal protein as the average American (including two pounds of casein-filled dairy per day)—yet don’t exhibit higher rates of any diseases Campbell ascribes to animal foods?

Why does Campbell point out the relationship between cholesterol and colorectal cancer (+33) but not mention the much higher relationship between sea vegetables and colorectal cancer (+76)? (For any researcher, this alone should be a red flag to look for an underlying variable creating misleading correlations, which—in this case—happens to be schistosomiasis infection.)

Why does Campbell fail to mention that plant protein intake correlates positively with many of the “Western diseases” he blames cholesterol for—including +19 for colorectal cancers, +12 for cervix cancer, +15 for leukemia, +25 for myocardial infarction and coronary heart disease, +12 for diabetes, +1 for breast cancer, and +10 for stomach cancer?

Of course, these questions are largely rhetorical. Only a small segment of “The China Study” even discusses the China Study, and Campbell set out to write a publicly accessible book—not an exhaustive discussion of every correlation his research team uncovered. However, it does seem Campbell overlooked or ignored significant points when discerning the overriding nutritional themes in the China Project data.

What about casein?

Along with trends gleaned from the China Project, Campbell recounts the startling connection he found between casein (a milk protein) and cancer in his research with lab rats. In his own words, casein “proved to be so powerful in its effect that we could turn on and turn off cancer growth simply by changing the level consumed” (page 5 of “The China Study”). Protein from wheat and soy did not have this effect.

This finding is no doubt fascinating. If nothing else, it suggests a strong need for more research regarding the safety of casein supplementation in humans, especially among bodybuilders, athletes, and others who use isolated casein for muscle recovery. Unfortunately, Campbell extrapolates this research beyond its logical scope: He concludes that all forms of animal protein have similar cancer-promoting properties in humans, and we’re therefore better off as vegans. This claim rests on several unproven assumptions:

- The casein-cancer mechanism behaves the same way in humans as in lab rats.

- Casein promotes cancer not just when isolated, but also when occurring in its natural food form (in a matrix of other milk substances like whey, bioactive peptides, conjugated linoleic acid, minerals, and vitamins, some of which appear to have anti-cancer properties).

- There are no differences between casein and other types of animal protein that could impose different effects on cancer growth/tumorigenesis.

How does Campbell justify generalizing the effects of casein to all forms of animal protein? Much of it is based on a study he helped conduct: “Effect of dietary protein quality on development of aflatoxin B[1]-induced hepatic preneoplastic lesions,” published in the August 1989 edition of the Journal of the National Cancer Institute. In this study, he and his research crew discovered that aflatoxin-exposed rats fed wheat gluten exhibited less cancer growth than rats fed the same amount of casein. But get this: When lysine (the limiting amino acid in wheat) was restored to make the gluten a complete protein, the rats had just as much cancer occurrence as the casein group. Jeepers!

Campbell thus deduced that it’s the amino acid profile itself responsible for spurring cancer growth. Because most forms of plant protein are low in one or more amino acids (called “limiting amino acids”) and animal protein is complete, Campbell concluded that animal protein, but not plant protein, must encourage cancer growth. Time to whip out the veggie burgers!

Of course, this conclusion has some gaping logical holes when applied to real life. Unless you consume nothing but animal products, you’ll be ingesting a mixed ratio of amino acids by default, since animal foods combined with plant foods still yield limiting amino acids. The rats in Campbell’s research consumed casein as their only protein source, the equivalent of someone eating zero plant protein for life. An unlikely scenario, to be sure.

Moreover, certain combinations of vegan foods (like grains and legumes) have complementary amino acid profiles, restoring each other’s limiting amino acid and resulting in protein that’s complete or nearly so. Would these food combinations also spur cancer growth? How about folks who pop a daily lysine supplement after eating wheat bread? If Campbell’s conclusions are correct, it would seem vegans could also be subject to the cancer-promoting effects of complete protein, even when eschewing all animal foods.

Also, it seems Campbell never mentions an obvious implication of a casein-cancer connection in humans: breast milk, which contains high levels of casein. Should women stop breastfeeding to reduce their children’s exposure to casein? Did nature really muck it up that much? Are children who are weaned later in life at increased risk for cancer, due to a longer exposure time the casein in their mothers’ milk? It does seem strange that casein, a substance universally consumed by young mammals, is so hazardous for health—especially since it’s designed for a time in life when the immune system is still fragile and developing.

At any rate, Campbell’s theories about plant versus animal protein and cancer are essentially speculation. Despite a single experiment with restoring lysine to wheat gluten, he hasn’t actually offered evidence that all animal protein behaves the same way as casein.

But check this out. After delineating his discovery of the link between casein and cancer, Campbell writes:

We initiated more studies using several different nutrients, including fish protein, dietary fats and the antioxidants known as cartenoids. A couple of excellent graduate students of mine, Tom O’Conner and Youping He, measured the ability of these nutrients to affect liver and pancreatic cancer. (Page 66)

So he did experiment with an animal protein besides casein! Unfortunately, Campbell never mentions what the specific results of this research were. In describing the studies he conducted with his grad students, Campbell says only that a “pattern was beginning to emerge: nutrients from animal-based foods increased tumor development while nutrients from plant-based foods decreased tumor development.” (Page 66)

I don’t know about you, but I’d sure like to see the actual data for some of this.

After a little searching, I found one of the aforementioned experiments conducted by Campbell, his grad student Tom, and two other researchers. It was published in the November 1985 issue of the Journal of the National Cancer Institute: “Effect of dietary intake of fish oil and fish protein on the development of L-azaserine-induced preneoplastic lesions in the rat pancreas.”

(A preneoplastic lesion, by the way, is a fancy term for the growth that occurs before a tumor.)

In this study, Campbell and his team studied three groups of carcinogen-exposed rats: One fed casein plus corn oil, one fed fish protein plus corn oil, and one fed fish protein plus fish oil (from a type of high omega-3 fish called menhaden). All groups received a diet of about 20% protein and 20% fat and ate the same amount of calories.

Providing background for the study, the authors note that previous research has showed fish protein to have anti-cancer properties (emphasis mine):

Gridley et al. [n15,n16] reported on two studies in which intake of fish protein resulted in a reduced tumor yield when compared to other protein sources. Spontaneous mammary tumor development in C3H/HeJ mice was reduced. The incidence of herpes virus type 2-transformed cell-induced tumors in mice was also reduced in animals fed a fish protein diet.

Perhaps this should’ve tipped Campbell off that not all sources of animal protein spur cancer growth like casein does. For reference, the cited studies are “Modification of herpes 2-transformed cell-induced tumors in mice fed different sources of protein, fat and carbohydrate” published in the November-December 1982 issue of Cancer Letters, and “Modification of spontaneous mammary tumors in mice fed different sources of protein, fat and carbohydrate” published in the June 1983 issue of Cancer Letters.

So what were the results of Campbell’s experiment? According to the study, both the casein/corn oil and fish protein/corn oil groups had significant preneoplastic lesions. We don’t know whether to blame this on the protein or the corn oil, since—according to the researchers—“intake of corn oil has previously been shown to promote the development of L-azaserine-induced preneoplastic lesions in rats.” However, the group that ate fish protein plus fish oil exhibited something radically different:

It is immediately apparent that menhaden oil had a dramatic effect both on the development in the number and size of preneoplastic lesions. The number of AACN per cubic centimeter and the mean diameter and mean volume were significantly smaller in the F/F [fish protein and fish oil] group compared to the F/C [fish protein and corn oil] group. Furthermore, no carcinomas in situ were observed in the F/F group, whereas the F/C group had an incidence of 3 per 16 with 6 total carcinomas.

There’s some significant stuff here, so let’s break this down point by point.

One: The cancer-inducing properties of fish protein, if there are any to begin with, were neutralized by the presence of fish oil. This means that even if all animal protein behaves like casein under certain circumstances, its effect on cancer depends on what other substances accompany it. Animal protein is therefore not a universal cancer promoter; only a situational one, at best.

Two: What does “fish protein” plus “fish fat” start to resemble? Whole fish. Campbell just demonstrated that animal protein may, indeed, operate differently when consumed with its natural synergistic components.

Since there wasn’t a rat group eating casein plus fish oil, we don’t know what the effect of a dairy protein plus fish fat would have been. However, it would be interesting to have more studies looking at cancer growth in mice fed diets of casein plus milk fat. If casein loses its cancer-promoting abilities under that circumstance, as fish protein did with fish oil, then we’d have good reason to think the various factions of whole animal products might reduce any cancer-promoting properties a single component has in isolation.

And Campbell and his team conclude:

[A] 20% menhaden oil diet, rich in omega 3 fatty acids, produced a significant decrease in the development of both the size and number of preneoplastic lesions when compared to a 20% corn oil diet rich in omega 6 fatty acids. This study provides evidence that fish oils, rich in omega 3 fatty acids, may have potential as inhibitory agents in cancer development.

Remember how Campbell said, summarizing this research, that “nutrients from animal-based foods increased tumor development while nutrients from plant-based foods decreased tumor development”? Last I checked, fish oil ain’t no plant food.

Why does Campbell avoid mentioning anything potentially positive about animal products in “The China Study,” including evidence unearthed by his own research? For someone who has openly censured the nutritional bias rampant in the scientific community, this seems a tad hypocritical.

But back to casein and milk for a moment. It’s interesting that the only dairy protein Campbell experimented with was casein, since whey—the other major protein in milk products—repeatedly shows cancer-protective and immunity-boosting effects, including when tested side-by-side with casein. Just a sampling of the literature:

- Diets containing whey proteins or soy protein isolate protect against 7,12-dimethylbenz(a)anthracene-induced mammary tumors in female rats. ” When 100% of the casein-fed rats had at least one tumor, soy-fed rats had a lower tumor incidence (77%) in experiment B (P < 0.002), but not in experiment A (P < 0.12), and there were no differences in tumor multiplicity. Whey-fed rats had lower mammary tumor incidence (54-62%; P < 0.002) and multiplicity (P < 0.007) than casein-fed rats in both experiments. … Furthermore, whey appears to be at least twice as effective as soy in reducing both tumor incidence and multiplicity.” (So much for plant protein being more protective against cancer!)

- Developmental effects and health aspects of soy protein isolate, casein, and whey in male and female rats. We found that SPI [soy protein isolate] accelerated puberty in female rats (p < .05) and WPH [whey protein hydrolysate] delayed puberty in males and females, as compared with CAS (p < .05). … Female rats fed SPI or WHP or treated with genistein had reduced incidence of chemically induced mammary cancers (p < .05) compared to CAS controls, with WHP reducing tumor incidence by as much as 50%, findings that replicate previous results from our laboratory.

- Tp53-associated growth arrest and DNA damage repair gene expression is attenuated in mammary epithelial cells of rats fed whey proteins. “Results indicate that mammary glands of rats fed a WPH [whey protein hydrolysate] diet are more protected from endogenous DNA damage than are those of CAS [casein]-fed rats.”

- A role for milk proteins and their peptides in cancer prevention. “Animal models, usually for colon and mammary tumorigenesis, nearly always show that whey protein is superior to other dietary proteins for suppression of tumour development.”

- A bovine whey protein extract stimulates human neutrophils to generate bioactive IL-1Ra through a NF-kappaB- and MAPK-dependent mechanism. “Our data suggest that WPE [whey protein extract] … has immunomodulatory properties and the potential to increase host defenses.”

- Whey proteins in cancer prevention.

- Whey protein concentrate (WPC) and glutathione modulation in cancer treatment.

I’ll let you be the judge.

In summary and conclusion…

Apart from his cherry-picked references for other studies (some of which don’t back up the claims he cites them for), Campbell’s strongest arguments against animal foods hinge heavily on:

- Associations between cholesterol and disease, and

- His discoveries regarding casein and cancer.

Even if the correlations with cholesterol did remain after adjusting for these risk factors, it takes a profound leap in logic to link animal products with disease by way of blood cholesterol when the animal products themselves don’t correlate with those diseases. If all three of these variables rose in unison, then hypotheses about animal foods raising disease risk via cholesterol could be justified. Yet the China Study data speaks for itself: Animal protein doesn’t correspond with more disease, even in the highest animal food-eating counties—such as Tuoli, whose citizens chow down on 134 grams of animal protein per day.

Nor is the link between animal food consumption and cholesterol levels always as strong as Campbell implies. For instance, despite eating such massive amounts of animal foods, Tuoli county had the same average cholesterol level as the near-vegan Shanyang county, and a had a slightly lower cholesterol than another near-vegan county called Taixing. (Both Shanyang and Taixing consumed less than 1 gram of animal protein per day, on average.) Clearly, the relationship between animal food consumption and blood cholesterol isn’t always linear, and other factors play a role in raising or lowering levels.

For #2, Campbell’s discoveries with casein and cancer, his work is no doubt revelatory. I give him props for dedicating so much of his life to a field of disease research that wasn’t always well-received by the scientific community, and for pursuing so ardently the link between nutrition and health. Unfortunately, Campbell projects the results of his casein-cancer research onto all animal protein—a leap he does not justify with evidence or even sound logic.

As ample literature indicates, other forms of animal protein—particularly whey, another component of milk—may have strong anti-cancer properties. Some studies have examined the effect of whey and casein, side-by-side, on tumor growth and cancer, showing in nearly all cases that these two proteins have dramatically different effects on tumorigenesis (with whey being protective). A study Campbell helped conduct with one of his grad students in the 1980s showed that the cancer-promoting abilities of fish protein depended on what type of fat is consumed alongside it. The relationship between animal protein and cancer is obviously complex, situationally dependent, and bound with other substances found in animal foods—making it impossible extrapolate anything universal from a link between isolated casein and cancer.

On page 106 of his book, Campbell makes a statement I wholeheartedly agree with:

Everything in food works together to create health or disease. The more we think that a single chemical characterizes a whole food, the more we stray into idiocy.

It seems ironic that Campbell censures reductionism in nutritional science, yet uses that very reductionism to condemn an entire class of foods (animal products) based on the behavior of one substance in isolation (casein).

In sum, “The China Study” is a compelling collection of carefully chosen data. Unfortunately for both health seekers and the scientific community, Campbell appears to exclude relevant information when it indicts plant foods as causative of disease, or when it shows potential benefits for animal products. This presents readers with a strongly misleading interpretation of the original China Study data, as well as a slanted perspective of nutritional research from other arenas (including some that Campbell himself conducted).

In rebuttals to previous criticism on “The China Study,” Campbell seems to use his curriculum vitae as reason his word should be trusted above that of his critics. @)

It’s no surprise “The China Study” has been so widely embraced within the vegan and vegetarian community: It says point-blank what any vegan wants to hear—that there’s scientific rationale for avoiding all animal foods. That even small amounts of animal protein are harmful. That an ethical ideal can be completely wed with health. These are exciting things to hear for anyone trying to justify a plant-only diet, and it’s for this reason I believe “The China Study” has not received as much critical analysis as it deserves, especially from some of the great thinkers in the vegetarian world. Hopefully this critique has shed some light on the book’s problems and will lead others to examine the data for themselves.

http://rawfoodsos.com/2010/06/09/a-closer-look-at-the-china-study-fish-and-disease/

[/FONT]

[h=1]ONE YEAR LATER: THE CHINA STUDY, REVISITED AND RE-BASHED[/h]

[FONT="]Since I’m not a vegan anymore, I figure it’s okay for me to beat dead horses. And also to resurrect the ones I buried last year and wallop on their half-rotten, fly-infested carcasses with my fists a few more times. So wallop I will: This post is dedicated to driving a couple more nails into the China Study coffin—and is aimed particularly at the folks out there who would rather listen to peer-reviewed research than some girl with a blog.[/FONT]

[FONT="]So my dear readers, hecklers, and spambots, I present to you a collection of peer-reviewed papers based on the China Study data that contradict or conflict with Campbell’s interpretation in his book, “The China Study.” Some studies you may have seen before; others will be new. Regardless, you can rest assured that these papers—some co-authored by Campbell himself—are by folks generally considered qualified in their field, and that, contrary to the “animal foods are harmful and cholesterol is associated with all Western diseases” message we received in “The China Study,”* other perspectives of the data abound.[/FONT]

[FONT="]*It’s also worth noting that”The China Study”—the one written by Campbell and published by BenBella Books—is not peer reviewed. Shockingly, neither are BenBella’s other books, including “You Don’t Talk About Fight Club,” “Seven Seasons of Buffy,” and “The Psychology of Harry Potter.” Contrary to what’s apparently popular belief, books—even health books—don’t have to pass under the scrutiny of peer review before they hit the stands. Hence why this exists.[/FONT]

[FONT="]But first, a few words on peer review[/FONT]

[FONT="]I want to burst the Peer-Review Bubble of Perfection before we get much further.[/FONT]

[FONT="]Peer review might be the best we’ve got right now—but it’s far from infallible, and its biases are no secret. In an article from 2000, Richard Horton—editor of the uber-peer-reviewed journal “The Lancet”—wrote some rather scathing comments about the peer-review system, stating that it is “biased, unjust, unaccountable, incomplete, easily fixed, often insulting, usually ignorant, occasionally foolish, and frequently wrong.” Even peer-reviewed journals have published papers on the problems with peer review (e.g., this article in “Nature”).[/FONT]

[FONT="]To top that off, history is speckled with some disturbing cases of research fraud that slipped right through the peer-review system. The best example is Scott Reuben, once considered a pioneer in the field of anesthesiology and pain management, who concocted at least 21 “studies” that were pure works of fiction—and managed to get all of them published in peer-reviewed journals. Over the years, he accepted big bucks from pharmaceutical companies to conduct studies on drugs like Celebrex and Effexor, but instead of actually enrolling patients, he made up some numbers and slid his nonexistent findings into major publications. And as it turns out, many of the drugs he convinced the world were beneficial were either ineffective of downright harmful. (You can see a list of his falsified peer-reviewed papers here.)[/FONT]

[FONT="]That’s an extreme example, but it illustrates the point. Even peer-reviewed papers should be taken with a grain of salt instead of held as gospel.[/FONT]

[FONT="]And with that, here are some papers to mull over. The bolded parts within quotes are to highlight the relevant bits.[/FONT]

[FONT="]Erythrocyte fatty acids, plasma lipids, and cardiovascular disease in rural China by Fan Wenxun, Robert Parker, Banoo Parpia, Qu Yinsheng, Patricia Cassano, Michael Crawford, Julius Leyton, Jean Tian, Li Junyao, Chen Junshi, and T. Colin Campbell.[/FONT]

[FONT="]A study involving fat, cholesterol, and cardiovascular disease? Surely they must be talking about how all that nasty saturated fat in animal foods clogs your arteries, right? Oh, snap:[/FONT]

[FONT="]So if you don’t want to take my word for it, take the word of this peer-reviewed paper: The China Study data showed no correlation between cholesterol and heart disease, but did find wheat and polyunsaturated fats to be mighty suspect.[/FONT]

[FONT="]Association of dietary factors and selected plasma variables with sex hormone-binding globulin in rural Chinese women (PDF) by Jeffrey R. Gates, Banoo Parpia, T. Colin Campbell, and Chen Junshi.[/FONT]

[FONT="]Wheat-fearers, you’ll enjoy this one.[/FONT]

[FONT="]This study focuses on sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), a molecule sometimes used to test for insulin resistance. (Higher levels are associated with better insulin sensitivity; lower levels are associated with insulin resistance and diabetes.) After fishing out associations between SHBG, fasting insulin, triglycerides, testosterone, and a number of diet and lifestyle variables, the researchers found:[/FONT]

[FONT="]Since I’m not a vegan anymore, I figure it’s okay for me to beat dead horses. And also to resurrect the ones I buried last year and wallop on their half-rotten, fly-infested carcasses with my fists a few more times. So wallop I will: This post is dedicated to driving a couple more nails into the China Study coffin—and is aimed particularly at the folks out there who would rather listen to peer-reviewed research than some girl with a blog.[/FONT]

[FONT="]So my dear readers, hecklers, and spambots, I present to you a collection of peer-reviewed papers based on the China Study data that contradict or conflict with Campbell’s interpretation in his book, “The China Study.” Some studies you may have seen before; others will be new. Regardless, you can rest assured that these papers—some co-authored by Campbell himself—are by folks generally considered qualified in their field, and that, contrary to the “animal foods are harmful and cholesterol is associated with all Western diseases” message we received in “The China Study,”* other perspectives of the data abound.[/FONT]

[FONT="]*It’s also worth noting that”The China Study”—the one written by Campbell and published by BenBella Books—is not peer reviewed. Shockingly, neither are BenBella’s other books, including “You Don’t Talk About Fight Club,” “Seven Seasons of Buffy,” and “The Psychology of Harry Potter.” Contrary to what’s apparently popular belief, books—even health books—don’t have to pass under the scrutiny of peer review before they hit the stands. Hence why this exists.[/FONT]

[FONT="]But first, a few words on peer review[/FONT]

[FONT="]I want to burst the Peer-Review Bubble of Perfection before we get much further.[/FONT]

[FONT="]Peer review might be the best we’ve got right now—but it’s far from infallible, and its biases are no secret. In an article from 2000, Richard Horton—editor of the uber-peer-reviewed journal “The Lancet”—wrote some rather scathing comments about the peer-review system, stating that it is “biased, unjust, unaccountable, incomplete, easily fixed, often insulting, usually ignorant, occasionally foolish, and frequently wrong.” Even peer-reviewed journals have published papers on the problems with peer review (e.g., this article in “Nature”).[/FONT]

[FONT="]To top that off, history is speckled with some disturbing cases of research fraud that slipped right through the peer-review system. The best example is Scott Reuben, once considered a pioneer in the field of anesthesiology and pain management, who concocted at least 21 “studies” that were pure works of fiction—and managed to get all of them published in peer-reviewed journals. Over the years, he accepted big bucks from pharmaceutical companies to conduct studies on drugs like Celebrex and Effexor, but instead of actually enrolling patients, he made up some numbers and slid his nonexistent findings into major publications. And as it turns out, many of the drugs he convinced the world were beneficial were either ineffective of downright harmful. (You can see a list of his falsified peer-reviewed papers here.)[/FONT]

[FONT="]That’s an extreme example, but it illustrates the point. Even peer-reviewed papers should be taken with a grain of salt instead of held as gospel.[/FONT]

[FONT="]And with that, here are some papers to mull over. The bolded parts within quotes are to highlight the relevant bits.[/FONT]

[FONT="]Erythrocyte fatty acids, plasma lipids, and cardiovascular disease in rural China by Fan Wenxun, Robert Parker, Banoo Parpia, Qu Yinsheng, Patricia Cassano, Michael Crawford, Julius Leyton, Jean Tian, Li Junyao, Chen Junshi, and T. Colin Campbell.[/FONT]

[FONT="]A study involving fat, cholesterol, and cardiovascular disease? Surely they must be talking about how all that nasty saturated fat in animal foods clogs your arteries, right? Oh, snap:[/FONT]

Within China neither plasma total cholesterol nor LDL cholesterol was associated with CVD [cardiovascular disease]. … The results indicate that geographical differences in CVD mortality within China are caused primarily by factors other than dietary or plasma cholesterol.

There were no significant correlations between the various cholesterol fractions and the three mortality rates [coronary heart disease, hypertensive heart disease, and stroke]. In contrast, plasma triglyceride had a significant positive association with CHD and HHD but not with stroke.

[FONT="]We’ve even got a cameo appearance from wheat again:[/FONT]There were no significant correlations between the various cholesterol fractions and the three mortality rates [coronary heart disease, hypertensive heart disease, and stroke]. In contrast, plasma triglyceride had a significant positive association with CHD and HHD but not with stroke.

The consumption of wheat flour and salt (the latter measured by a computed index of salt intake and urinary sodium excretion) was positively correlated with all three diseases [cardiovascular disease, hypertensive heart disease, and stroke].

[FONT="]And for those of your leery of industrial oils and polyunsaturated fats, check this out:[/FONT]

Unlike what might be expected from studies on Western subjects, there was no significant inverse correlation between RBC-PC total PUFAs and CVD mortality; in fact, RBC-PC total PUFAs, especially the n-6 fatty acids, were positively correlated with CHD [coronary heart disease] and HHD [hypertensive heart disease].

[FONT="]That one was a little acronym-y, but basically it says that higher levels of polyunsaturated fats (especially omega-6 fats) in red blood cells was associated with more heart disease.[/FONT]

[FONT="]So if you don’t want to take my word for it, take the word of this peer-reviewed paper: The China Study data showed no correlation between cholesterol and heart disease, but did find wheat and polyunsaturated fats to be mighty suspect.[/FONT]

[FONT="]Association of dietary factors and selected plasma variables with sex hormone-binding globulin in rural Chinese women (PDF) by Jeffrey R. Gates, Banoo Parpia, T. Colin Campbell, and Chen Junshi.[/FONT]

[FONT="]Wheat-fearers, you’ll enjoy this one.[/FONT]

[FONT="]This study focuses on sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), a molecule sometimes used to test for insulin resistance. (Higher levels are associated with better insulin sensitivity; lower levels are associated with insulin resistance and diabetes.) After fishing out associations between SHBG, fasting insulin, triglycerides, testosterone, and a number of diet and lifestyle variables, the researchers found:[/FONT]

The principal positive food-SHBG correlates in order of magnitude were rice (0.61, P < 0.0001), green vegetables (0.49, P < 0.001), fish (0.42, P < 0.001), and meat (0.38, P < 0.05). The strongest negative food correlate with SHBG (positively correlated with insulin) was wheat (-0.57, P < 0.0001).

[FONT="]In other words, the foods associated with higher SHBG (and lower insulin) were rice, green veggies, fish, and meat. The main food associated with lower SHBG (and higher insulin) was… dun dun dun… wheat. Not only do we have vindication of some animal foods, but we also have another red flag whipping up over our favorite glutenous grain. Although the link with meat diminished in more sophisticated statistical models, the other foods kept their associations with SHGB—and wheat proved to be the strongest predictor of low SHBG, while rice was the strongest predictor of higher SHBG. In discussing their findings, the researchers note that wheat seemed to accompany a number of markers for poor health:[/FONT]

Significant differences in the diet of rural Chinese populations studied suggest that wheat consumption may promote higher insulin, higher triacylglycerol, and lower SHBG values. Such a profile is consistent with that commonly associated with obesity, dyslipidemia, diabetes, hypertension, and heart disease. On the other hand, the intake of rice, fish, and possibly green vegetables may elevate SHBG concentrations independent of weight or smoking habits.

[FONT="]It looks like the post I wrote on wheat and heart disease in the China Study was old news: Campbell and his colleagues already spotted the link back in 1996! But why would wheat have such a vastly different effect than rice? The paper offers a possible explanation:[/FONT]

The effect of rice and wheat on SHBG was remarkable and unexpected. … Nevertheless, there is some evidence to suggest that rice and wheat can have significantly different effects on the biochemical variables we measured. Panlasigui et al (58) found that the high-amylose rice varieties had blood glucose responses that were lower than those of wheat bread. Other varieties, particularly “converted” rice, gave considerably higher values. Miller et al (59) in comparing rice and wheat varieties found that the insulin index (II) was unusually low on the relative scale compared with the glycemic index (GI) of the same foods. For example, Calrose brown rice had a GI = 83 but an II = 51. White bread was used as the reference food (GI = 100, II = 100). Wheat may be unique in its relative capacity to stimulate insulin. Most recently, Behall and Howe (60) reported a significantly lower insulin response curve area in both normal and hyperinsulinemic men consuming a high-amylose diet. The relative differences in the fatty acid proportions and/or amylose content for wheat and rice may thus be responsible for modulating serum SHBG, triacylglycerols, and insulin.

[FONT="]Although it’s still speculative, the amount of amylose (a component of starch) and relative proportion of fatty acids in wheat might make it more problematic than other grains like rice—especially in terms of raising triglycerides and fasting insulin while lowering SHBG. Which is particularly interesting in the context of this paper, because in one of his responses to my critique, Campbell stated:[/FONT]

[The] correlation of wheat flour and heart disease is interesting but I am not aware of any prior and biologically plausible and convincing evidence to support an hypothesis that wheat causes these diseases, as you infer.

[FONT="]Go figure![/FONT]