From the darkest days of his presidential campaign in Iowa in November, to his string of primary victories this winter, the anthem that kicked off John F. Kerry's rallies, whether there were 100 voters in a union hall or 1,000 filling a gymnasium, was Bruce Springsteen's war cry of resolve, "No Surrender."

No more. Running 40 minutes late to a Kansas City rally Wednesday evening, the presumptive Democratic nominee bounded onto the stage pumping fists to his favorite song of late, Chuck Berry's celebration of "a country boy named of Johnny B. Goode."

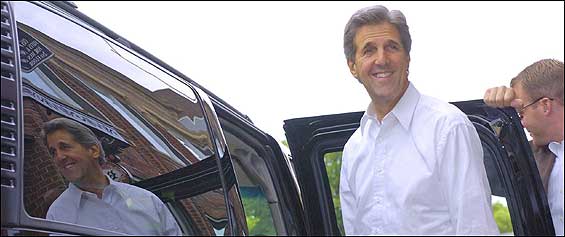

No matter the criticism he takes from the pundits, no matter the daily slings he absorbs from the Bush campaign, Kerry gives all the appearances of riding high after a year of hard campaigning for a job he has sought for 30 years. Gone, at least for now, are the bags under his eyes, the rambling asides in his speeches, the crummy hotels of a cash-strapped campaign, the occasional utterances of annoyance. Kerry, who says "discipline" is the watchword of his candidacy today, is evincing confidence -- some Republicans say hubris -- as he insists that his "better ideas" will trump President Bush's "inept" foreign policy. His skeptics, he says, are simply making the same mistake as those who wrote off his candidacy before his primary landslides.

And yet: Kerry's campaign events also belie the campaign's nervousness. Uncontrollable events could damage Kerry, just as the Iraq prisoner abuse scandal and economic uncertainties have brought Bush's approval ratings to historic lows.

One sign of this was the minidrama that unfolded in the Missouri crowd Wednesday as Kerry spoke just 50 feet away. Two Bush supporters in the audience, clapping flip-flops over their heads to symbolize Republican attacks on Kerry's alleged policy shifts, were purposely blocked from view by 10 firefighters waving Kerry signs.

The firefighters, whose union has endorsed Kerry, were also in the way of dozens of voters trying to get a glimpse of Kerry.

"We can't see!" yelled 22-year-old student Kathryn Zimmerman.

"We're doing our job. We're doing our job," replied one firefighter, who refused to give his name.

Three Kerry aides told of the dispute said the campaign was not responsible. Moments later, a firefighter snatched a flip-flop from Phil Ishmael, a financial planner, and refused to give it back.

"I guess they don't think John can handle any dissent," Ishmael said after the rally. "We just wanted to celebrate John's flexibility on Iraq, tax cuts, gay marriage. You name it."

The theatrics of the evening, increasingly common in some form at Kerry events now, were also the sort that are increasingly unwelcome for a campaign that is sticking to a rigid, controlled script. Daily, Kerry aides refuse requests from his national traveling press corps for press conferences, where questions might detract from the campaign's message of the day; Kerry takes questions about once every three weeks. On Thursday the campaign declined to have Kerry comment on CIA director George J. Tenet's resignation, releasing a statement instead, even though Kerry previously called for him to step down. On Wednesday, aides refused to have him comment when news broke that Bush had talked to a private lawyer about a grand jury investigation into alleged White House leaks.

Kerry prefers talking to local media about local concerns, which tend to yield favorable headlines. And he takes care to get seven or eight hours of sleep, unlike the five or fewer a night before the Iowa caucuses. He has begun putting on weight, after looking rail-thin for weeks during the primaries. During a visit Tuesday to Sloan's Ice Cream Parlor in West Palm Beach, he ordered "a great big, thick coffee milkshake" and then turned to foreign policy adviser Graham Allison and said, "It's going from here right to here," motioning from his mouth to his waistline.

The Kerry campaign's summer strategy is all about pacing, building credibility, and husbanding his energy in preparation for an all-out push against Bush in the fall. Kerry wants to be like a Tour de France racer who stays close to the leader, riding in his slipstream, and then bursts ahead at the end. Yet some Democrats say that Kerry could benefit from a looser, more outgoing style and a greater willingness to speak from the heart, like a Bill Clinton or a John McCain, to present an alternative vision for the country, instead of relying to a degree on "anybody but Bush" sentiments.

"Spontaneity is not encouraged in politics today, but spontaneity often means genuineness and authenticity to people, and being genuine is so essential in this race," said Dan Glickman, a former Clinton agriculture secretary who now leads the Institute of Politics at Harvard's Kennedy School. "It's hard for a long-term sitting US senator to be very spontaneous. On the other hand, the status quo has not been a killer for him; he's either ahead or tied in most polls."

Friday's announcement that 248,000 jobs were created in May, beating most expectations, and the appointment of an interim Iraqi government could contribute to a Bush surge in the days ahead, political analysts say, while Kerry's choice of a vice president this summer is expected to give him a lift. Kerry aides are also counting on his debate performance and his reputation as a strong closer.

At rallies recently, Kerry has pointed out that the Bush campaign had spent $60 million in six weeks, $70 million in seven weeks, and $80 million in eight weeks on negative advertisements painting him as untrustworthy, pessimistic, and liberal. At the same time, a May 12 Pew poll suggested that Kerry was leading Bush, 50 percent to 45 percent, while a May 23 Washington Post-ABC news poll indicated they were tied at 46 percent each, offering reasons for both camps to feel good after a spring of damaging commercials and political controversy.

"I don't think there's any candidate in history who has taken a $75 million punch from his rival and is arguably better off," said Carter Eskew, a senior strategist to 2000 Democratic nominee Al Gore. "Kerry has shown over the years that he is a slow starter and a strong closer. But he has reason to feel confident; pessimism is toxic and metastasizing, and you cannot underestimate the importance of projecting confidence."

Nowhere did Kerry learn that lesson better than in Iowa. In November and December, Kerry and his staff would buck one another up as one poll after another suggested he was badly trailing former Vermont governor Howard Dean and Missouri's Richard A. Gephardt. The senator hired a new campaign manager, Mary Beth Cahill, who gave him confidence with her dictum, "Everything is about the candidate." At the time, Kerry said that he could tell in his gut when political races couldn't be won and that he didn't feel that way about himself.

Yet some early mornings and some late evenings, as he decompressed on his Iowa bus, there was worry etched in his brow and uncertainty in his small talk that indicated he was aware that his candidacy could turn out differently.

As mid-January approached, however, Kerry began declaring that he was "great" and "energized" whenever he was asked how he felt.

Still, the next day, when scores of journalists arrived for a Kerry rally in Des Moines to witness an unscripted, last-minute reunion between the senator and a former Green Beret whose life Kerry had saved in Vietnam, the senator appeared to lose a little color from his face as he regarded the swarm from his bus window. He did not seem quite ready for all the attention, quipping to his group of nine traveling reporters: "I wish I could just stay in here with my friends."

Those days ended, more or less, when Kerry touched down in New Hampshire on the morning after his surprise Iowa victory, still declaring himself an underdog, but increasingly seen as the favorite for the Democratic nomination. The signs of hesitancy and nerves mostly disappeared; instead Kerry seemed to draw energy and confidence from the growing crowds, and he impressed voters who had seen Dean and Gephardt as the firebrands in the race, until they dropped out.

"All we knew was how good Gephardt was, and a lot of us felt surprised and impressed that Kerry came to rallies and didn't talk over people's heads, didn't talk at them, but tried to get into a deeper conversation with them," said May Scheve Reardon, the Democratic Party chairwoman in Missouri, a battleground state that Bush carried in 2000.

Boston Globe.